- Basic Principles in the Management of Acute Burn Injuries in Adults

Diese Übersichtsarbeit gibt einen Überblick über die aktuellen, stadiengerechten Behandlungsmethoden für Verbrennungen, wie sie am Nationalen Verbrennungszentrum des Universitätsspitals Zürich praktiziert werden. Damit sollen Praktikerinnen und Praktiker Empfehlungen für die Behandlung von akuten leichten bis schweren Verbrennungen bekommen, die auf wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen und der langjährigen Erfahrung des Verbrennungszentrums basieren. Das Hauptaugenmerk liegt auf einem praktischen Leitfaden und den verschiedenen Optionen, die neue, innovative konzeptionelle Ansätze beinhalten.

Schlüsselwörter: Verbrennungsverletzung, Beurteilung einer Verbrennung, akutes Verbrennungsmanagement, prähospitale Verbrennungsbehandlung, Versorgung von Brandwunden

Introduction

The treatment of burn injuries is a continuously evolving medical field. According to the Swiss Council for Accident Prevention, around 7970 burns caused by fire or heat occur every year in Switzerland. Other common burns include scalds from boiling water and thermal injuries from electrical accidents, the latter being characterized by a high mortality rate. In addition, around 11 360 people in Switzerland are treated for poisoning and chemical burns on an annual basis [1].

The present article provides a concise overview of the methods practiced at the National Burn Center of the University Hospital Zurich for the treatment of acute burn injuries, focusing on practical guidelines and innovative approaches based on a long-standing experience and amended by scientific evidence.

In Switzerland, severely burned patients are treated in accordance with the decision of the Intercantonal Agreement on Highly Specialized Medicine (HSM decision-making body) [2]. Consequently, it is important to respect criterias for referral to HSM-appointed centers following an initial survey by the primary care provider [2, 3]. The two Swiss centers in charge of the management of adult burn patients are the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois in Lausanne (Centre Universitaire Romand des Brûlés, CURB) and the University Hospital Zurich (Burn Center).

Criteria for patient referral to a burn center are primarily complex burns including patients with superficial dermal burns affecting over 20 % of their total body surface area (TBSA) in adults or over 10 % in seniors.

Additional criteria are [2]:

• Patients needing burn shock resuscitation

• Burns on critical areas of the body, such as the face, hands, genitalia, or major joints

• Deep partial thickness burns and full thickness burns

• Circumferential burns

• Burns with accompanying trauma or disease that may complicate treatment, affect mortality, or extend recovery

• Inhalation injuries

• Any burns with treatment uncertainty

• Patients with burns requiring emotional, social or rehabilitation support

• Electrical or chemical burns

• Patients with burns and associated diseases (e.g., toxic epidermal necrolysis, necrotizing fasciitis) should be referred if affected skin area is 10 % (elderly) or 15 % (adults)

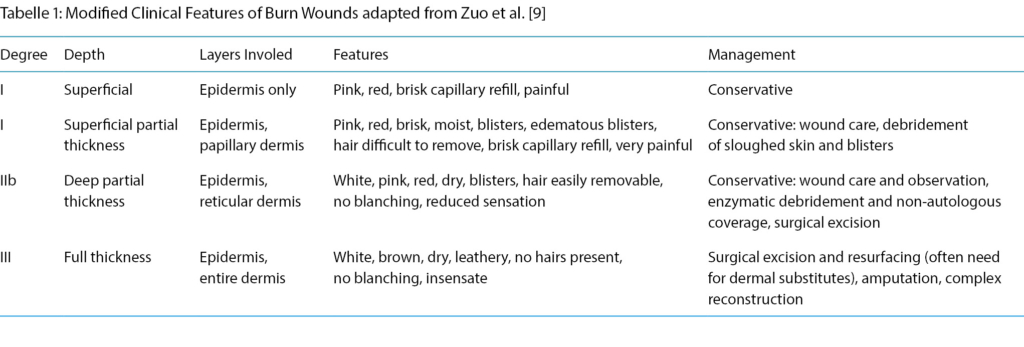

Depth of burn injury

Two fundamental burn-specific factors are decisive for the assessment of the severity of a thermal wound: burn depth, area and extent of burn injury. The depth of the damage is dictated by the temperature and duration of exposure and is classified into first-, second-, third-degree burns, which ultimately determines the respective surgical or conservative therapy (Table 1). In a first-degree burn, the top epidermal layer of skin is damaged. A painful redness of the skin develops. Blisters are pathognomonic for second-degree burn, which are subdivided into 2a and 2b burns. Type 2a burns comprise damages to the epidermis and superficial dermis, and show a painful pink to red wound bed with prompt recapillarization. In type 2b burns, which involve deeper dermal layers, the wound beds are by contrast whitish with no recapillarization upon pressure, and less painful. In a third-degree burn, the entire epidermis and dermis are irrevocably damaged. A dry, leather-like texture with whitish to brownish color is characteristic. As pain receptors are also affected, complete loss of sensation is observed. First- and third-degree burns are usually easy to differentiate clinically, while the assessment of second-degree burns remains challenging. As the differentiation of 2a and 2b burn injuries is essential for subsequent treatment strategies, knowledgable burn wound evaluation by healthcare providers is essential [4, 5].

Besides the clinical evaluation, technological advancement has aided in burn depth assessment. Laser Doppler technology (moor instruments, Devon, UK) for example, is a useful, painless method for measuring blood flow using the Doppler effect [6]. As described by Park et al., the laser Doppler technique is a useful method to predict the depth of a wound in burn patients and thus allows an early treatment decision [6, 7, 8]. Furthermore, the study by Hop et al. reported both cost savings and a minimization of healing time [8]. In our Burn Center, the laser Doppler is a standard equipment utilized for precise appraisal and documentation of burn depth, especially in mixed second-degree burns.

The extent of the burn injury

Aside from burn depth, estimation of the affected burn area is paramount and remains a challenge in the clinical setting when practiced by unexperienced personnel. The Wallace Score or Rule of Nines is used to estimate the surface area of a burn. It is expressed as percentage of body surface area and was, while still the gold standard today, already developed by Pulaski and Tennison in 1947 and published by Alexander Wallace [10]. The score provides the basis for calculating intravascular fluid requirements, which is particularly necessary in severe burns where there is destruction of the skin barrier and therefore increased fluid loss.

The body is divided into areas of 9 % of the body surface: 9 % for the head and arms, 18 % for the abdomen, back and each of the legs. The genitals are counted as 1 %. As an alternative, the Lund and Browder table was proposed [11].

After evaluating 14 studies in the Review of Thom et al., the Wallace rule was identified as the best method for calculating TBSA. For minor burns, the palm rule proved to be extremely helpful, especially for less experienced clinicians when first assessing the extent of the wound. For the calculation of the TBSA, the hand, excluding fingers and wrist, represents 1 % of the body surface [12, 13].

However, several studies proposed that an adjustment of the Rule of Nines should be based on different body proportions, age, body mass index and other patient-specific factors, otherwise there might be a misinterpretation of the extent of burn injuries [13, 14]. In obese patients, the TBSA of the trunk is estimated to be 50 %, legs 30 %, arms 14 %, and head 6 % of the overall area. In patients with android fat distribution, in which adipose tissue accumulates predominantly as visceral fat, as well as in patients with gynecologic physiques, TBSA should be adjusted accordingly [14]. Lund and Browder›s table considers different body proportions and the age of the patient for calculating body surface area. However, Nichter et al. found that overestimations of an average of 12.4 % occurred [15].

Furthermore, another study demonstrated that in obese patients weighing more than 80 kg, a Rule of Five provided better results in determining the total percentage of burned area. Due to differences in body proportions and the relatively large head, the rule of eight proved more useful for estimating the total area affected in infants weighing less than 10 kg [13, 14].

To address the over- and underestimation of the extent of burn injuries, the implementation of digital solutions such as software-based assessment was proposed. There are standardized three-dimensional human models adjusted for weight, age, height, and sex. The extent and depth of the burn are drawn virtually onto the prefabricated model by the physician, and the TBSA is then automatically calculated by the software, providing a more standardized burn area estimation [13, 16].

Besides the modifications and novel developments as mentioned above, the Rule of Nine is still the most commonly applied method for a quick estimation of burn extent, and therefore is recommended for practitioners outside major burn centers for the estimation of adult burns.

The impact of the burned area on the outcome is illustrated by the Abbreviated Burn Severity Index (ABSI score), where the burn area is one of the main factors for patient mortality. The ABSI score developed by Tobiasen et al. in 1982 is a prognostic score still commonly used to predict survival based on various clinical parameters of burn patients [17]. However, Bartels et al. later demonstrated that the prognostic ABSI score does no longer reliably predict the chance of survival for patients as the mortality of the ABSI score was overestimated especially in patients with severe burns. The discrepancy between observed and ABSI score-predicted survival probability was deemed multifactorial. For instance, female patients received an additional point in the ABSI score due to their gender, resulting in a worse outcome, even though this was not necessarily in line with the observed survival probability. Also, instead of a linear relationship, an exponential relationship between age and survival probability was assumed, and the score modified accordingly [18, 19].

Fluid substitution

Let us now discuss a consistently difficult topic in the acute management of burn patients, which is fluid resuscitation. The Parkland formula describes the quantity of fluids, usually lactated Ringer›s, that should be administered during the first 24 hours after suffering a burn, comprising the following equation: 4 ml/kg/%TBSA fluid [20, 21]. The first half of the calculated volume of fluid should be administered within the first eight hours after the event. The remaining volume should follow over a subsequent period of 16 hours. Lactated Ringer is preferred as a crystalloid fluid, as it can successfully counteract burn-induced hypovolemia as well as a deficit of sodium. Although no contraindications are currently known, close volume monitoring should be performed especially in patients with heart failure as well as in patients with severe kidney disease [20, 21, 22].

A retrospective study by Blumetti et al. found that over a period of 15 years 48 % of patients who received Parkland formula-based rehydration were overhydrated. However, only 12 % of adequately rehydrated patients and 14 % of overhydrated patients in this study actually met the criteria for use of the Parkland formula. The authors therefore proposed the formula should only be a starting point for rehydration and that during the course of rehydration urinary output is the essential parameter to ensure patient survival [23]. In the study, patients who received a fluid volume calculated according to the Parkland formula showed a lower mortality rate in the first week, but ultimately, restrictive fluid substitution was associated with a lower mortality rate than Parkland’s liberal fluid regime [24, 25]. In the intensive care unit of our Burn Center, the Utah protocol is implemented for fluid management, which adapts fluid resuscitation according to urine output, with 30–50 ml/h serving as a benchmark. The fluid intake is then dynamically increased or decreased depending on the deficiency or surplus of urine output generated within defined observation times [26].

Hypothermia

Severe burns often result in a dramatic decrease of body temperature, so that appropriate patient preparation from the earliest moment is crucial. Apart from the destruction of the insulating skin barrier and associated fluid loss, the enzymatic reaction has been shown to lead to a reactive decrease in core temperature and an increase in the metabolic rate as a compensation mechanism. Furthermore, hypothermia results in increased oxygen consumption, catabolic response and blood loss, making body temperature monitoring essential for at-risk patients [27, 28]. This counteracts an increase in mortality and morbidity rates and can significantly affect the course of treatment, especially in severely burned patients [29, 30, 31]. Various strategies can be applied to maintain normothermia and can be divided in external and internal heat sources. Foremost, prolonged, overzealous cooling should be avoided to prevent hypothermia, particularly in children. External methods include chemical or electrical heated blankets, radiant heaters, and the use of thermal insulation, especially for the extremities and the head. An increase in the temperature of the hydrotherapy and operating room is often needed. Internal heat sources may include blood or intravenous fluid warmers [27]. In addition, the esophageal heat exchanger tube (EHT) system is another innovative tool that adds to temperature management during surgery using an esophageal probe. In our experience, the EHT is an effective method for preventimg hypothermia and its complications, especially in the treatment of severe burns [32]. The risk of hypothermia associated to thermal injury directly correlates with the size of the affected area. Certain patient groups are at higher risk of developing hypothermia during the course of the procedure [29]. In a study conducted by Loenecker et al., only burn injury patients who were anesthetized or artificially ventilated developed hypothermia [33]. This certainly demonstrates indirectly the severity of the associated burns, requiring intubation. In addition, the risk increases with age and an elevated severity index score, as well as a Glasgow Coma Scale below 8 [30, 34]. In addition to expeditious surgery, a continuous exchange between surgeons, nurses and anesthesiologists is needed for a joint effort to control hypothermia.

Conservative Treatment

Conservative treatment is indicated for I- and IIa-degree burns as well as for limited IIb or even small III-degree burns. For I-degree burns analgesia and application of a moisturizing ointment like Bepanthen® (Bayer AG, Basel, CH) is usually sufficient. If there is uncertainty about the depth of the burn, specifically scalding, a temporary dressing is applied before wounds are re-assessed the following day. Several products are available on the market, but we would like to mention those that are most frequently utilized in our department for conservative treatment. Mepitel® (Mölnlycke Health Care GmbH, Wien, AUT) is a silicone-coated, non-adhesive dressing which is permeable to exuding wounds [35, 36]. In a study by Bugmann and Gotschall et al. silicone-coated nylon dressings were compared with silver sulfadiazine (SSD) [37, 38]. It was found that the re-epithelialization of the wound was faster when silicone-coated nylon dressings were used. Using the visual Analog Scale, a study conducted by Gotschall et al. demonstrated that patients treated with silicone-coated nylon dressings reported less pain than those treated with SSD [38]. Bugmann et al. also reported that fewer dressing changes were necessary when silicone-coated nylon dressings were used [37]. In our clinical routine, Mepitel® is indicated for IIa-degree burns or mixed pattern burns that require re-evaulation. In the latter case, we leave Mepitel® for up to ten days with no or merely superficial dressing change. In case wound healing is not completed, surgery can be performed after this period.

Suprathel® (Polymedics Innovation, Denkendorf, DE) is an absorbable microporous membrane and is approved as an alloplastic skin substitute for the treatment of second-degree burns, second-degree burns with third-degree components and split skin donor sites [39, 40, 41]. In 2007 Suprathel® has also been approved for the treatment of facial burns. The anti-microbial effect of Suprathel® is caused by the lactic acid which reaches a pH of 5.5–4.5 on the wound bed. While this damages microbes, there is no toxicity to the epithelial cells, which creates good conditions for irritation-free healing and good cosmetic results [42]. Ideally, it only needs to be applied once and does not require any further dressing changes during the healing phase of the skin [39, 43]. For superficial second-degree burns in the very delicate facial region the use of Suprathel® is recommended as it not only increases wound healing but also shortens hospital stay and thereby the costs as demonstrated in a study by Merz et al. [42]. Moreover, both Uhlig et al. and Schwarze et al. used the visual analog scale to evaluate the pain sensation of patients after the application of Suprathel® dressings. They reported that compared to other dressings the sensation of pain was reduced after the application of Suprathel® [39, 41, 44]. In our unit, Suprathel® is used for extensive 2a ° burn injuries in all areas. Care has to be taken that wounds are adequately decontaminated before application. Post-application handling is pivotal to avoid premature removal of Suprathel® and therefore is generally performed by experienced personnel. Ialugen Plus® (IBSA Institut Biochimique SA, Lamone, CH) consists of sodium hyaluronate and silver sulfadiazine and has a positive effect on re-epithelialization as well as an antibacterial and local analgetic effect. Faster re-epithelialization and wound healing was achieved with the combination of hyaluronic acid and silver sulfadiazine in second-degree burns compared to silver sulfadiazine alone [45, 46]. It should be noted that Ialugen Plus® does make the interpretation of a burned wound bed difficult at times due to an adhesive layer that forms on the wound bed. Nevertheless, Ialugen Plus® still is a valuable tool particularly for infected wounds or those prone to infection. Another indication are areas that are difficult to treat with dressings such as the genital area or the ear.

Standard surgical approach

Early excision and skin grafting, a concept established half a century ago, still remains the mainstay of burn surgery treatment in our burn department for third-degree burns and extensive 2b-degree burns [47]. Depending on the overall status of the patient, we target a rapid excision within the first 48–72 hours. If the dermal vascularization is preserved, a tangential excision can be performed with a standard dermatome. If the subdermal vascular plexus is no longer preserved, as found in third-degree burns, an epifascial excision that encompasses the entire subcutaneous tissue over the muscle fascia is a standard technique to be considered. Expanded autologous split thickness skin grafts serve as the gold standard for defect coverage (Figure 1). The surface of split thickness skin grafts is augmented by either the conventional mesh technique, or in cases of large burn areas by the Meek micrografting technique [48, 49, 50]. The latter approach is used for burn areas exceeding approximately 40 % of TBSA, although adjustments have to be made according to the overall status of the patient. In short, split thickness skin grafts are cut into 196 individual squares and loaded onto an expandable carrier gauze. By this technology, an expansion of up to 1:9 can be achieved. Non-expanded “sheet” split thickness skin grafts are our primary tool for cosmetically or functionally relevant areas such as the face, neck and hands. Again, the overall general status of the patient dictates the treatment strategy, which means that for instance patients with limited skin graft donor sites may urge surgeons to apply meshed skin grafts for aforementioned areas.

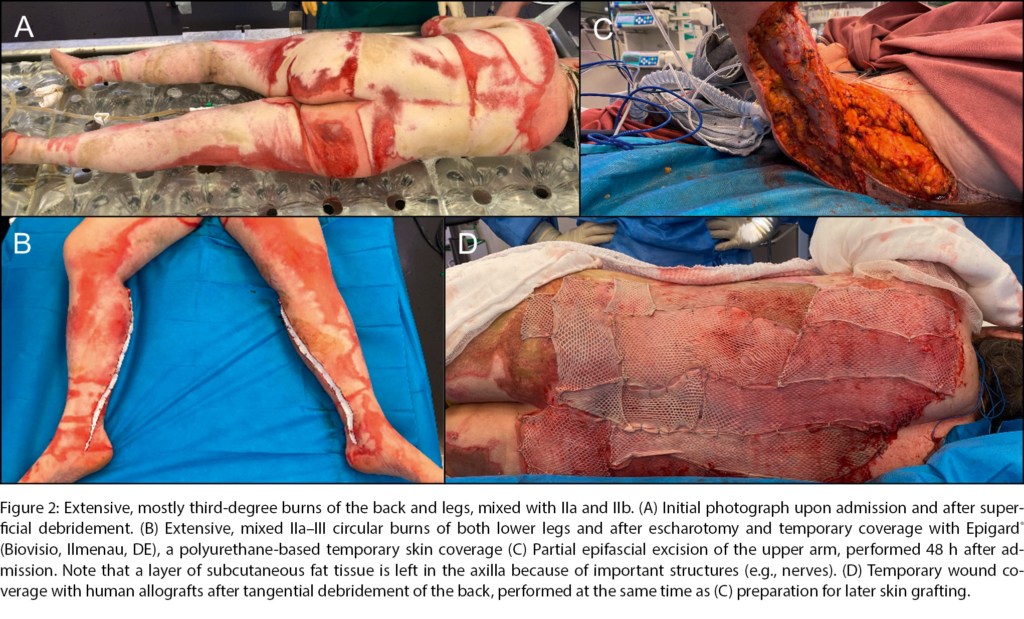

In most severe burn patients, a staged therapy with excision and temporary coverage is the preferred strategy (Figure 2). To this day, human allografts still are considered the gold standard by most burn surgeons to prepare wound beds in between excision and coverage [51]. This paradigm, however, is challenged as new products enter the market and may replace allografts in the future.

Special attention by primary care providers has to be directed towards circular burns, which may pose the threat of eschar-induced compartment syndrome. Especially in case of circumferential third-degree burns, an early escharotomy with incision of the constricting eschar may be imperative for affected limbs or the trunk (Figure 2B).

Enzymatic debridement and regenerative surgery

At our Burn Center, we are eager to aid technological advancements and provide opportunity to incorporate innovative solutions into our standard therapeutic repertoire. Some of the novel, less invasive burn wound management techniques that had an impact on our treatment algorithm will be shortly discussed next. One relatively new concept is the wound debridement via enzymes, which represents a feasible alternative to the classical excision. In this context, the pineapple strain-derived enzyme product named Nexobrid® (Diapharm GmbH & Co. KG, Muenster, DE) has revolutionized the debridement of thermally damaged necrotic tissue. The main advantage is a selective removal of necrotic tissue which preserves healthy dermis, whereas surgical excision always bears the risk of under- or over-excision [52]. The benefits, such as shortened hospitalization, reduced infection rates and a reduced need for transplantation, have already been demonstrated in multiple studies [53]. The underlying wound healing benefits include a statistically significant earlier macroscopical recovery of the dermis and better re-epithelialization after enzymatic debridement compared to the control group [34, 52, 53]. Also, the remaining dermis may serve as a natural scaffold for further autologous regenerative treatment, e.g. by skin cells or application of platelet-rich fibrin [54]. Nexobrid® is a key tool in the necrectomy of mixed pattern, 2b ° and limited 3 ° burn injuries. We were able to show recently that even extensive burns over > 15 % TBSA can be treated successfully. Finally, Nexobrid® is also a viable option for preventing invasive escharotomy, the invasive skin incision in case of circumferential constricting wounds, as reported above [54, 55]. Downsides or rather areas of caution for Nexobrid® application is the need for careful build-up of experience and – particularly in intensive care patients – a well-organized team of nurses, wound specialists and intensive care physicians. The primary assessment post-Nexobrid® debridement is pivotal as it directly impacts the further treatment plan as well as the subsequent wound care regimen.

Beyond the necrectomy, the introduction of skin substitutes has advanced the field of burn surgery in recent years.

As donor sites for STSGs are limited especially in cases of extensive burns, significant market developments have resulted in several novel products [56]. Dermal templates such as the long-known Integra® (Integra Biosciences AG, Zizers, CH) or the more recently introduced Novosorb BTM® (Polymedics Innovation Gmbh, Denkendorf, DE) can be beneficial for reconstructing lost dermis. In the acute phase they provide protection against loss of fluid and bacterial invasion [57]. Furthermore, a neodermis induced by the dermal templates is formed, which offers good results in terms of function as well as aesthetics [58, 59]. In the acute setting, dermal substitutes form a protective layer until autografting is performed approximately three weeks later, allowing previously harvested donor sites to heal in the meantime [60]. In addition, improved vascularization of the burn wound reduces graft rejection and allows the use of thinner autografts [61]. The true benefit of dermal substitutes is the introduction of a dermal layer that determines later functional outcome. Dermal substitutes therefore are principally considered for deep burn wounds after epifascial excision or tangential excision with exposure of fat tissue. In the latter case, we could observe that dermal substitutes can develop a vascularized layer eligible for skin grafts.

Within the context of dermal substitutes, a product named Kerecis® (Kerecis, Isafjordur, IS) is worth mentioning. Kerecis® is a decellularized fish skin matrix containing proteins and lipids including Omega 3, which was shown to shorten the healing time of donor sites after skin grafting when compared to other temporary dressings [62, 63]. Also, Kerecis® can be readily combined with Nexobrid®, outlining a novel regenerative treatment axis [64]. Kerecis® pursues a unique sustainability-oriented corporate strategy as it is manufactured from scrapped fish skin with resource-conscious technologies.

Finally, cell-based regenerative medicine is a profoundly important, future-oriented cornerstone in burn surgery. Cultured epithelial autografts (CEAs), i.e., keratinocytes harvested from a small split thickness skin sample and expanded in in vitro cultures, have been part of the standard treatment to accelerate re-epithelialization of most extensive burn wounds for many decades. CEAs unfold their true potential in extensive burn wounds with limitations in donor site areas, where they are implemented as an adjunct to skin grafts [65, 66]. Beyond CEAs, our Burn Center participates in prospective randomized clinical trials to investigate the feasibility of constructs of epidermis-dermis cultured on collagen matrices that would permit the reconstruction of full thickness skin [67]. Cultured epidermis-dermis constructs may provide true solutions for extensive, deep burn wounds and burn scars.

Flap surgery

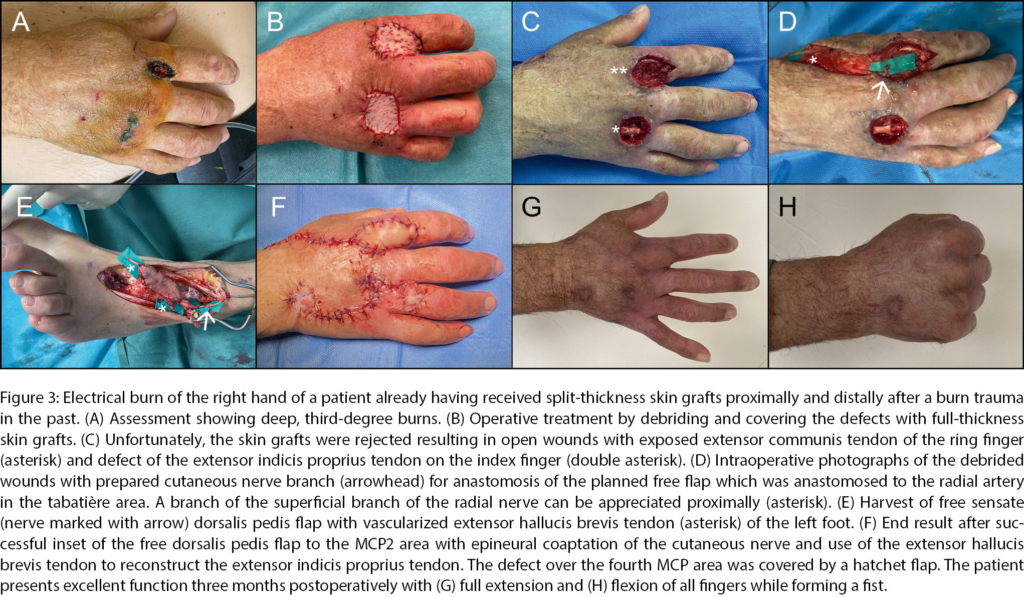

For certain burn wounds, e.g., with exposure of functionally relevant anatomic structures such as nerves, major blood vessels, bones and joints and crucial tendons, the defect coverage via flaps is advocated. Reports from the past, such as by Platt et al., who documented that only 9 of 604 patients treated at a tertiary burn center required free tissue transfer, showed little leeway for flap surgeries [68]. The classic reconstructive ladder (a popular principle in plastic surgery that proposes options for defect coverage from simple to most difficult technique in stepwise manner) and its variations proposed paradigms for tissue reconstruction with the focus on the simplicity of the applied means [69]. In a dynamic era with frequent changes in technologies and techniques, stiff paradigms appear somewhat obsolete, as previously suggested [70]. With a tremendous growth of reconstructive and particularly microsurgical experience over the recent past, we believe that a personalized reconstructive approach catering to the respective needs of the individual burn patient is justified. Besides high-voltage injuries, which were the most common indication for flap surgery for burn patients in the past, reconstructive flaps now are a robust element in our surgical toolbox for any thermal injury [68, 71, 72]. The consequences are often extensive injuries with exposure and loss of nerves, vascular structures, tendons, and bones. The choice of flap depends on various factors. Localization, the size and depth of the defect, and the structures to be reconstructed must first be assessed [68, 73]. Although classical muscle flaps such as the latissimus dorsi or gracilis flaps still are eligible, thin perforator flaps such as the profunda artery perforator (PAP), superficial circumflex artery perforator (SCIP), dorsalis pedis (Figure 3) and especially the anterolateral thigh s-(ALT) flap offer attractive alternatives with less donor site morbidity and therefore are the primary flaps of choice for burn reconstruction.

Free flaps play a special role in electrical burns. Electricity causes the formation of pores in the membranes of cells known as “electroporation”, which contributes to quick and extensive necrosis of tissue [74]. The necrosis is typically progressive, therefore the full extent of injury may only be understood by several rounds of debridement. Patients often develop compartment syndrome due to tissue edema, and the affected tissue usually has damaged blood vessels resulting in avascularity leading to further necrosis [75].

That means the timing of a free flap reconstruction is an important issue in electrical burn injuries. The subject remains debatable: some argue that the timing does not affect flap survival [71]. Others have gone even as far as to claim that an early reconstruction could limit tissue loss [76] and lead to better outcome and function [77]. On the other hand, some authors have reported an increased risk of flap loss in early reconstruction [78, 79]. A study of our Burn Center revealed the use of 14 free microvascular tissue transfers between 2005 and 2019. Of these 14 free flaps 5 were performed early between 5 to 21 days after initial trauma, with two of these resulting in flap loss [80]. An example of a free microvascular tissue reconstruction of the hand using a dorsalis pedis flap in combination with a local hatchet flap executed at our center can be seen in Figure 3. In conclusion, free microvascular flaps represent an important tool for plastic-reconstructive surgeons when treating electrical burn injuries; however, the patient as well as the indication have to be selected carefully and one should consider the potential impact of timing when planning such complex reconstructions in these heavily traumatized patients.

Conclusion

In the management of acute burn patients, existing basic principles with regard to assessment of burn depth and TBSA as well as concomitant trauma/diseases are vital to a successful treatment course. Early consultation and referral to burn centers is advised to prevent procrastinated therapy with potential devastating consequences. The Burn Center of the University Hospital Zurich aims to align established surgical principles such as early excision and skin grafting with new regenerative medical techniques and reconstructive microsurgery to foster innovation in this challenging field of medicine.

Abbreviations

ABS Abbreviated Burn Severity Index

HSM Highly Specialized Medicine

SSD Silver sulfadiazine

TBSA Total-Body-Surface-Area

Department of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery

University Hospital Zurich

Rämistrasse 100

8091 Zurich

Switzerland

bong-sung.kim@usz.ch

Historie

Manuscript accepted: 20.02.2023

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest exist.

Dr. Bong-Sung Kim, M.D.

Department of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery

University Hospital Zurich

Potential referral to a Swiss burn center should be considered during initial assessment of a burn injury.

The Wallace rule and degree classification provides the most important evaluation for the extent and severity of burn injuries.

Preventing hypothermia is of utmost importance, given its negative effects on mortality and morbidity.

Fluid resuscitation is crucial, and the Parkland formula should be followed as a guideline, however, the substi-tution should also be adjusted during the course of treatment to prevent under- or overhydration.

Burn injuries with unclear depth should be bandaged temporarily to allow a reevaluation the following day

and/or by a specialist in a Burn Center.

Besides classical treatment patterns, regenerative

medicine and microsurgery are valuable tools in the surgical toolbox of burn surgeons.

Learning Questions

1. Which of the following burn injuries should be

transferred to a burn center? (Multiple answers)

a) Second-degree burns 5 % of the thigh

b) High-voltage injuries

c) Inhalation burns

d) Second-degree burn injuries of the hand

2. Which statements regarding burn injuries are correct? (Multiple answers)

a) 2a-degree burns are not painful.

b) Recapillarization is compromised in deep

second-degree (IIb) burns.

c) Third-degree burns affect the epidermis and

the entire dermis.

d) 2b-degree burns are not painful, and hairs remain

adherent to the dermis.

1. Niemann S, Achermann Stürmer Y, Derrer P, Ellenberger L. Status 2022: Statistik der Nichtberufsunfälle und des Sicherheitsniveaus in der Schweiz. 2022. https://www.bfu.ch/de/ die-bfu/doi-desk/10-13100-bfu-2-399-01-2021; last access: 10.09.2022.

2. Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen und ‑direktoren (GDK). Reevaluation der HSM-Leistungszuteilungen im Bereich der schweren Verbrennungen beim Erwachsenen. 2013. https://www.gdkcds.ch/fileadmin/docs/public/gdk/themen/ hsm/hsm_spitalliste/201311_01a_bb_dc_burns_20131127_ def_d.pdf; last access: 01.01.2023.

3. Jester I, Jester A, Demirakca S, Waag KL. Notfallmanagement bei der Primärversorgung kindlicher Verbrennungen. Intensivmed Notfallmed. 2005;42(1):60–65.

4. Dries DJ. Burn care: before the burn center. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28(1).

5. Deutschen Gesellschaft für Verbrennungsmedizin (DGV). Behandlung thermischer Verletzungen des Erwachsenen. 2021. https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/044-001l_ S2k_Behandlung-thermischer-Verletzungen-des-Erwachse nen_2021-07.pdf; last access: 10.09.2022.

6. Park DH, Hwang JW, Jang KS, Han DG, Ahn KY, Baik BS. Use of laser Doppler flowmetry for estimation of the depth of burns. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(6):1516–1523.

7. Shepherd AP, Öberg PÅ. Laser-Doppler Blood Flowmetry. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Basic Theory and Operating Principles of Laser Doppler Blood Flow Monitoring and Imaging (LDF & LDI), Issue 1; 1990 (ISBN 0-7923-0508-6).

8. Hop MJ, Hiddingh J, Stekelenburg C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of laser Doppler imaging in burn care in the Netherlands. BMC Surg. 2013;13(1).

9. Zuo KJ, Medina A, Tredget EE. Important Developments in Burn Care. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(1):120e–138e.

10. Wallace AB. The exposure treatment of burns. Lancet. 1951;1 (6653):501–504.

11. Williams RY, Wohlgemuth SD. Does the “rule of nines” apply to morbidly obese burn victims? J Burn Care Res. 2013;34(4):447– 452.

12. Thom D. Appraising current methods for preclinical calculation of burn size – A pre-hospital perspective. Burns. 2017;43 (1):127–136.

13. Moore RA, Waheed A, Burns B. Rule of Nines. StatPearls. 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513287/; last access: 02.09.2022.

14. Livingston EH, Lee S. Percentage of burned body surface area determination in obese and nonobese patients. J Surg Res. 2000;91(2):106–110.

15. Nichter LS, Williams J, Bryant CA, Edlich RF. Improving the accuracy of burn-surface estimation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76 (3):428–433.

16. Parvizi D, Giretzlehner M, Dirnberger J, et al. The use of telemedicine in burn care: development of a mobile system for TBSA documentation and remote assessment. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2014;27(2):94.

17. Tobiasen J, Hiebert JM, Edlich RF. The abbreviated burn severity index. Ann Emerg Med. 1982;11(5):260–262.

18. Bartels P, Thamm OC, Elrod J, et al. The ABSI is dead, long live the ABSI – reliable prediction of survival in burns with a modified Abbreviated Burn Severity Index. Burns. 2020;46(6):1272– 1279.

19. Tsurumi A, Que YA, Yan S, Tompkins RG, Rahme LG, Ryan CM. Do standard burn mortality formulae work on a population of severely burned children and adults? Burns. 2015;41(5):935– 945.

20. Mehta M, Tudor GJ. Parkland Formula. StatPearls. 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537190/; last access: 12.09.2022.

21. Haberal M, Sakallioglu Abali AE, Karakayali H. Fluid management in major burn injuries. Indian J Plast Surg. 2010; 43 (Suppl):S29–S36.

22. Zodda D. Calculated decisions: Parkland formula for burns. Emerg Med Pract. 2018;20(Suppl 2):S1–S2.

23. Blumetti J, Hunt JL, Arnoldo BD, Parks JK, Purdue GF. The Parkland formula under fire: is the criticism justified? J Burn Care Res. 2008;29(1):180–186.

24. Daniels M, Fuchs PC, Lefering R, et al. Is the Parkland formula still the best method for determining the fluid resuscitation volume in adults for the first 24 hours after injury? – A retrospective analysis of burn patients in Germany. Burns. 2021;47 (4):914–921.

25. Saffle JL. The phenomenon of “fluid creep” in acute burn resuscitation. JBCR. 2007;28:382–385. 26. Utha department of health. Utha EMS Protocoll Guideliness. 2020. Available from: https://bemsp.utah.gov/wp-content/up loads/sites/34/2020/03/2020-Utah-EMS-Protocol-Guidelines- Final.pdf; last access: 05.02.2023.

27. Bittner EA, Shank E, Woodson L, Martyn JAJ. Acute and perioperative care of the burn-injured patient. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(2):448–464.

28. Oda J, Kasai K, Noborio M, Ueyama M, Yukioka T. Hypothermia during burn surgery and postoperative acute lung injury in extensively burned patients. J Trauma. 2009; 66(6):1525–9.

29. Ziegler B, Kenngott T, Fischer S, Hundeshagen G, Hartmann B, Horter J, et al. Early hypothermia as risk factor in severely burned patients: A retrospective outcome study. Burns. 2019; 45(8):1895–1900.

30. Weaver MD, Rittenberger JC, Patterson PD, et al. Risk factors for hypothermia in EMS-treated burn patients. Prehospl Emerg Care. 2014;18(3):335–341.

31. Sherren PB, Hussey J, Martin R, Kundishora T, Parker M, Emerson B. Lethal triad in severe burns. Burns. 2014;40(8):1492– 1496.

32. Furrer F, Wendel-Garcia PD, Pfister P, Hofmaenner DA, Franco C, Sachs A. Perioperative targeted temperature management of severely burned patients by means of an oesophageal temperature probe. Burns. 2022;S0305-4179(22)00066-3.

33. Lönnecker S, Schoder V. [Hypothermia in patients with burn injuries: influence of prehospital treatment]. Chirurg. 2001;72 (2):164–167.

34. Singer AJ, Taira BR, Thode HC, McCormack JE, Shapiro M, Aydin A, et al. The association between hypothermia, prehospital cooling, and mortality in burn victims. Acad Emerg Med. 2010; 17(4):456–459.

35. Morris C, Emsley P, Marland E, Meuleneire F, White R. Use of wound dressings with soft silicone adhesive technology. Paediatr Nurs. 2009;21(3):38–43

36. Waring M, Bielfeldt S, Mätzold K, Wilhelm KP, Butcher M. An evaluation of the skin stripping of wound dressing adhesives. J Wound Care. 2011;20(9):412–422.

37. Bugmann P, Taylor S, Gyger D, et al. A silicone-coated nylon dressing reduces healing time in burned paediatric patients in comparison with standard sulfadiazine treatment: A prospective randomized trial. Burns. 1998;24(7):609–612.

38. Gotschall CS, Morrison MIS, Eichelberger MR. Prospective, randomized study of the efficacy of Mepitel on children with partial-thickness scalds. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1998; 19(4): 279–283.

39. Schwarze H, Küntscher M, Uhlig C, et al. Suprathel, a new skin substitute, in the management of partial-thickness burn wounds: results of a clinical study. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60 (2):181–185.

40. Uhlig C, Rapp M, Hartmann B, Hierlemann H, Planck H, Dittel KK. Suprathel-an innovative, resorbable skin substitute for the treatment of burn victims. Burns. 2007;33(2):221–229.

41. Uhlig C, Hierlemann H, Dittel K-K. Actual Strategies in the Treatment of Severe Burns – Considering Modern Skin Substitutes. Osteosynthesis Trauma Care. 2007;15(01):2–7.

42. Merz KM, Sievers R, Reichert B. Suprathel® bei zweitgradigoberflächlichen Verbrennungen im Gesicht. GMS Verbrennungsmed. 2011; 4:Doc01.

43. Nolte SV., Xu W, Rodemann H-P, Rennekampff H-O. Suitability of Biomaterials for Cell Delivery in Vitro. Osteosynthesis Trauma Care. 2007;15(01):42–47.

44. Uhlig C, Rapp M, Dittel KK. New strategies for the treatment of thermally injured hands with regard to the epithelial substitute Suprathel. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2007;39(5):314– 319.

45. Koller J. Topical treatment of partial thickness burns by silver sulfadiazine plus hyaluronic acid compared to silver sulfadiazine alone: a double-blind, clinical study. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2004;30(5–6):183–190.

46. Costagliola M, Agrosì M. Second-degree burns: A comparative, multicenter, randomized trial of hyaluronic acid plus silver sulfadiazine vs. silver sulfadiazine alone. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(8):1235–1240.

47. Janzekovic Z. A new concept in the early excision and immediate grafting of burns. J Trauma. 1970;10(12):1103–1108

48. Singh M, Nuutila K, Kruse C, Robson MC, Caterson E, Eriksson E. Challenging the Conventional Therapy: Emerging Skin Graft Techniques for Wound Healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136 (4):524e–530e.

49. Kadam D. Novel expansion techniques for skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2016;49(1):5–15.

50. Pallua N, Von Bülow S. Behandlungskonzepte bei Verbrennungen. Teil II: Technische Aspekte. Chirurg. 2006;77(2):179–188.

51. Paggiaro AO, Bastianelli R, Carvalho VF, Isaac C, Gemperli R. Is allograft skin the gold-standard for burn skin substitute? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2019;72(8):1245–1253.

52. Rosenberg L, Shoham Y, Krieger Y, et al. Minimally invasive burn care: a review of seven clinical studies of rapid and selective debridement using a bromelain-based debriding enzyme (Nexobrid®). Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2015;28(4):264.

53. Singer AJ, McClain SA, Taira BR, Rooney J, Steinhauff N, Rosenberg L. Rapid and selective enzymatic debridement of porcine comb burns with bromelain-derived Debrase: acute-phase preservation of noninjured tissue and zone of stasis. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31(2):304–309.

54. Waldner M, Ismail T, Lunger A, et al. Evolution of a concept with enzymatic debridement and autologous in situ cell and platelet-rich fibrin therapy (BroKerF). Scars Burn Heal. 2022;8:20595 131211052394. DOI: 10.1177/20595131211052394 [eCollection 2020 Jan–Dec.].

55. Grünherz L, Michienzi R, Schaller C, et al. Enzymatic debridement for circumferential deep burns: the role of surgical escharotomy. Burns. 2022;S0305–4179(22)00312–6.

56. Shakespeare P. Burn wound healing and skin substitutes. Burns. 2001;27(5):517–522.

57. Lohana P, Hassan S, Watson SB. IntegraTM in burns reconstruction: Our experience and report of an unusual immunological reaction. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2014;27(1):17.

58. Berger A, Tanzella U, Machens HG, Liebau J. Administration of Integra on primary burn wounds and unstable secondary scars. Chirurg. 2000;71(5):558–563.

59. Stern R, McPherson M, Longaker MT. Histologic study of artificial skin used in the treatment of full-thickness thermal injury. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1990;11(1):7–13.

60. Phillips GSA, Nizamoglu M, Wakure A, Barnes D, El-Muttardi N, Dziewulski P. The Use Of Dermal Regeneration Templates For Primary Burns Surgery In A UK Regional Burns Centre. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2020;33(3):245.

61. Heimbach D, Luterman A, Burke J, et al. Artificial dermis for major burns. A multi-center randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 1988;208(3):313–320.

62. Magnusson S, Baldursson BT, Kjartansson H, Rolfsson O, Sigurjonsson GF. Regenerative and Antibacterial Properties of Acellular Fish Skin Grafts and Human Amnion/Chorion Membrane: Implications for Tissue Preservation in Combat Casualty Care. Mil Med. 2017;182(S1):383–388.

63. Baldursson BT, Kjartansson H, Konrádsdóttir F, Gudnason P, Sigurjonsson GF, Lund SH. Healing rate and autoimmune safety of full-thickness wounds treated with fish skin acellular dermal matrix versus porcine small-intestine submucosa: a noninferiority study. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14(1): 37–43.

64. Wallner C, Holtermann J, Drysch M, Schmidt S, Reinkemeier F, et al. The Use of Intact Fish Skin as a Novel Treatment Method for Deep Dermal Burns Following Enzymatic Debridement: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Eur Burn J. 2022;3(1): 43–55.

65. ter Horst B, Chouhan G, Moiemen NS, Grover LM. Advances in keratinocyte delivery in burn wound care. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;123:18–32.

66. Mühlbauer W, Henckel von Donnersmarck G, Hoefter E, Hartinger A. [Keratinocyte culture and transplantation in burns]. Chirurg. 1995;66(4):271–276.

67. Biedermann T, Klar AS, Böttcher-Haberzeth S, Schiestl C, Reichmann E, Meuli M. Tissue-engineered dermo-epidermal skin analogs exhibit de novo formation of a near natural neurovascular link 10 weeks after transplantation. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30(2):165–172.

68. Platt AJ, McKiernan MV, McLean NR. Free tissue transfer in the management of burns. Burns. 1996;22(6):474–476.

69. Gottlieb LJ, Krieger LM. From the reconstructive ladder to the reconstructive elevator. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(7):1503– 1504.

70. Al Deek NF, Wei FC. It is the time to say good bye to the reconstructive ladder/lift and its variants. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70(4):539–540.

71. Jabir S, Frew Q, Magdum A, El-Muttardi N, Philp B, Dziewulski P. Microvascular free tissue transfer in acute and secondary burn reconstruction. Injury. 2015;46(9):1821–1827.

72. De Lorenzi F, Van der Hulst R, Boeckx W. Free flaps in burn reconstruction. Burns. 2001;27(6):603–612.

73. Gapany M. Failing flap. Facial Plast Surg. 1996;12(1):23–27.

74. Bryan BC, Andrews CJ, Hurley RA, et al. Electrical Injury, Part I: Mechanisms. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;21(3):IV.

75. Zelt RG, Daniel RK, Ballard PA, et al. High-voltage electrical injury: chronic wound evolution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82 (6):1027–1041.

76. Karimi H, Akhoondinasab MR, Kazem-Zadeh J, Dayani AR. Comparison of the results of early flap coverage with late flap coverage in high-voltage electrical injury. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2017;38(2):e568–e573.

77. Dega S, Gnaneswar SG, Rao PR, Ramani P, Krishna DM. Electrical burn injuries: Some unusual clinical situations and management. Burns. 2007;33(5):653–665.

78. Sauerbier M, Ofer N, Germann G, Baumeister S. Microvascular reconstruction in burn and electrical burn injuries of the severely traumatized upper extremity. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2007;119(2):605–615.

79. Baumeister S, Köller M, Dragu A, Germann G, Sauerbier M. Principles of microvascular reconstruction in burn and electrical burn injuries. Burns. 2005;31(1):92–98.

80. Pedrazzi N, Klein H, Gentzsch, et al. Predictors for limb amputation and reconstructive management in electrical injuries. Burns. 2022.

PRAXIS

- Vol. 112

- Ausgabe 10

- August 2023