- Workplace-Based Assessments in Postgraduate Specialist Palliative Medicine: a narrative review

Introduction

Experiential learning (i.e. learning by experience) is a key component of medical professionals’ training in which acquiring professional knowledge is mainly driven by workplace experience (1). Palliative care (PC) is an interprofessional specialty that focuses on relationships and communication. It is intended to improve the quality of life of patients with incurable and often unpredictable diseases (2).

Workplace-based assessments (WBAs) emerged from the observation that the intent of an assessment should be learning. WBAs are, therefore, assessments with a primary formative intent that, according to Norci et al. (3), have the following key elements: alignment with a training program that has competence as an outcome, timely feedback on a real work-related situation, and guidance for a trainee’s learning toward a desired competency.

Typical examples of direct (single-time-point) WBAs include the mini-clinical evaluation exercise (Mini-CEX), direct observation of procedural skills (DOPS), and case-based discussions. Mini-CEX and DOPS are in-training assessments wherein a supervisor conducts an in-person assessment of a trainee’s performance. For example, a supervisor observes a trainee during the disclosure of “bad news” and then gives feedback on his or her performance. Case-based discussions: In a case-based discussion, performance in a clinical situation is assessed retrospectively. For example, a supervisor discusses the strategy to change an opioid treatment with a trainee and provides feedback on the approach the trainee uses for solving this clinical problem (3).

WBAs are well-researched educational tools with various desirable effects. Independent of the WBA type, they have shown positive effects on the quality and frequency of feedback (4). However, the acceptance of these types of assessments as standard learning practices by healthcare professionals is not universal. Key barriers to acceptance include a) lack of time, b) low feedback quality, c) an unclear setting (formative vs. summative) that leads to fear of being assessed, d) lack of supervisor training, and e) challenges in the professional relationship between a supervisor and a trainee (4, 5).

Increasingly so-called Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) are introduced to define tasks learners have to be capable to manage. Further, many observations of such activities can be used to “entrust” a learner to manage such activities either with direct/indirect or without supervision (6).

There are two basic medical training models: 1) the traditional time-based one in which a trainee is judged to be competent after a fixed training period, and 2) competency-based medical education (CBME), which is a learner-centered model in which a trainee’s preparedness for independent practice is evaluated after a defined level of competency is reached.

In Switzerland, PC training is strongly anchored in the traditional time-based education model. A Swiss postgraduate specialist PC training program follows this model and is governed by the Swiss Society of Palliative Care (palliative.ch) and the Swiss Institute of Medical Education (SIWF) (7). It involves three years of residency, with two years spent in a certified PC unit, an accredited theoretical course (a minimum of 140 hours), and the fulfillment of practical competencies. The Swiss Society of PC provides specific learning goals and competencies (8). Concerning WBAs, providing four WBAs per year is a mandatory requirement for accreditation as a PC training unit, but no guidance on which specific WBAs should be used is given.

Although WBAs are a main component of competency-based education, the use of WBAs in postgraduate specialist PC settings has not been summarized in the literature. To address this gap, this current review was guided by the following question: What is the current evidence regarding WBAs in PC postgraduate physician training?

Closing this gap is of interest because, on a practical level, summarizing existing evidence could provide a scientific groundwork for countries that want to shift postgraduate specialist PC training toward more competency-based education (9). The current situation in Switzerland is typical of this transition and can serve as a practical example in the discourse surrounding this topic.

Methods

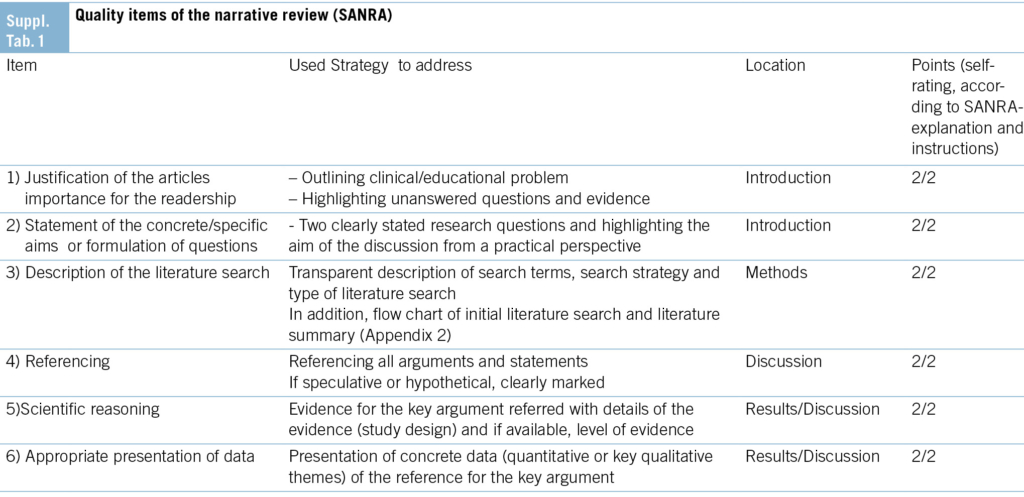

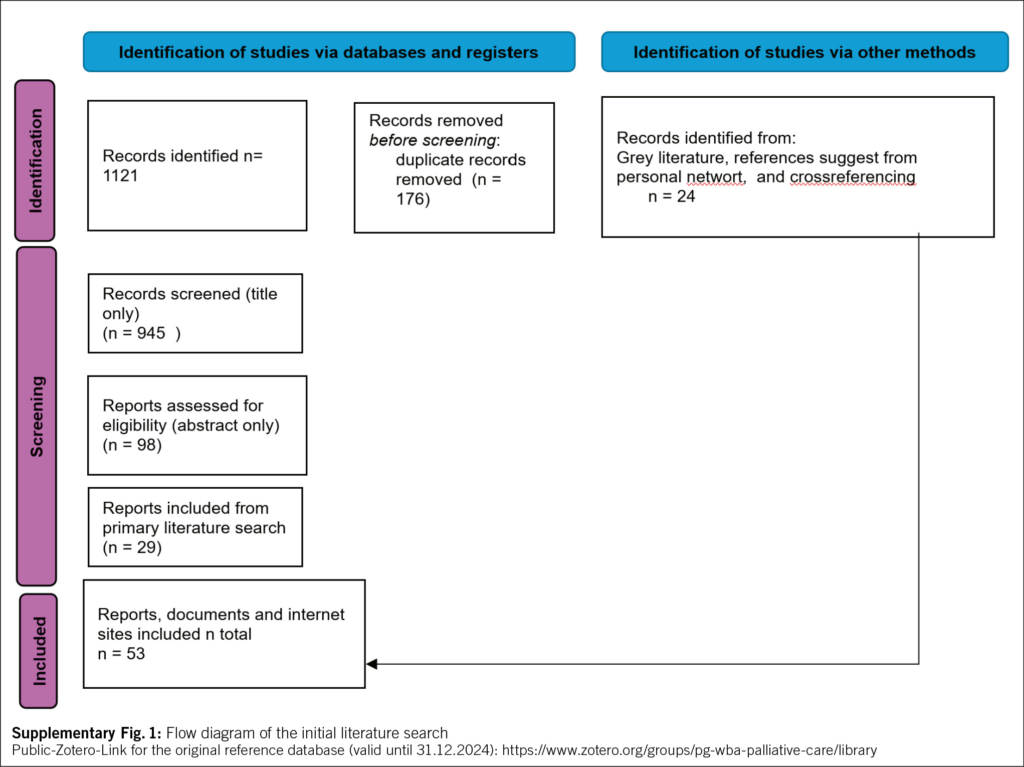

This narrative review followed elements of the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) (10). A detailed description can be found in Appendix 1, and the literature search is discussed in the following paragraph. To obtain an overview, an initial literature search was conducted in PubMed, Ovid, Scopus, ERIC, and PsychInfo. No limitations were set, and references up to November 2022 were included. The search focused on WBAs in postgraduate PC training using the following key search terms: PC, education, postgraduate, workplace-based assessment (as a general term), and specific types of WBAs.

After an initial search, the PubMed database was monitored for new publications on “education” in “palliative care” (search alert). Additionally, a Google Scholar search (“workplace-based assessment” AND “postgraduate training” AND “specialist PC”) was conducted in February 2024. After the initial search, emerging literature in the ongoing literature survey and specific references to underline emerging key statements were directly referenced in the text.

Information about the Swiss system is based on the official accreditation and quality requirements of the Swiss Society of Palliative Care (8). Details of the initial literature search and reference selection process can be found in Appendix 2 and a summary of the initial literature in Appendix 3.

Results

In total, 1121 papers were identified via an initial literature search conducted in November 2022. Twenty-nine papers were included after their abstracts were assessed for eligibility. An additional 24 references were found in the gray literature via crossreferencing. This resulted in 53 references, which served as the foundation for this review. Within these papers, specific evidence regarding postgraduate PC training in general was found in 31 records (11–41). The variety of papers was broad, ranging from reviews, reports, and surveys to policy papers (standards and requirements) on residency training programs. The evidence base for WBAs in specialist PC was enhanced by gray literature and personal communications; the search returned seven papers, documents, and internet websites (42–48). The literature survey and final Google Scholar search in 2024 identified three additional papers.(49–51)

Workplace-based Assessment in Specialist PC

We mainly found descriptions of the implementation of WBAs in specialist PC programs. Most of these programs followed a CBME model of training. In these programs, WBAs are the key elements of training and are, therefore, comprehensively implemented and described. In time-based systems (e.g., Switzerland), WBAs are usually considered a choice for supporting training, among others.

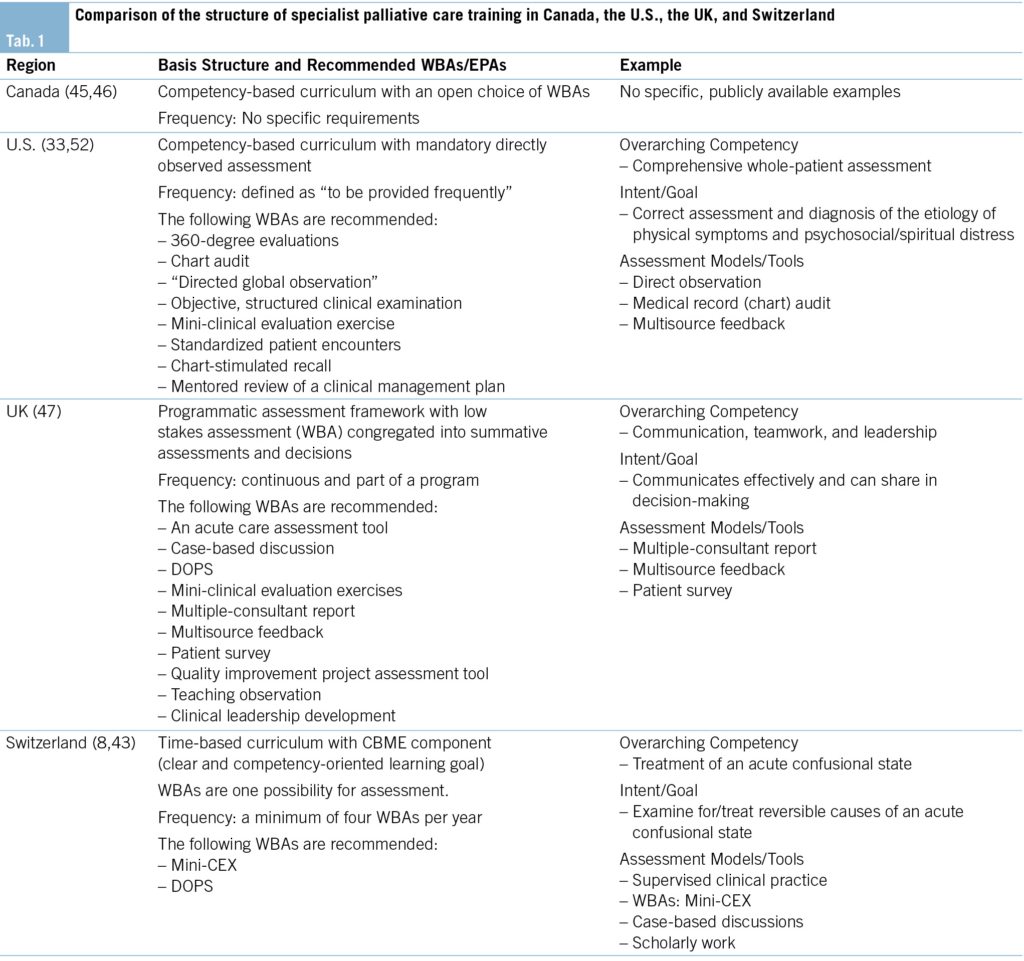

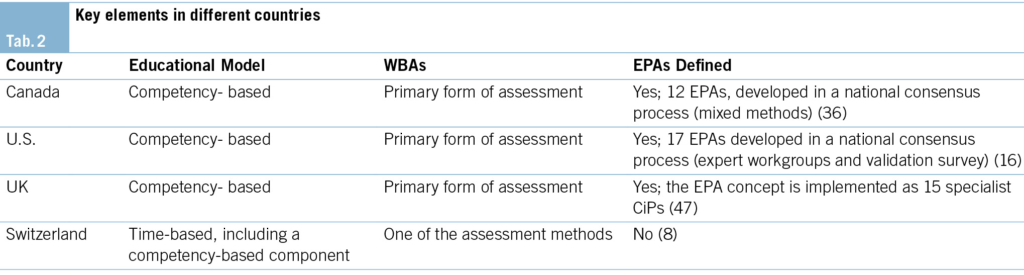

This review chose three CBME-pioneer countries as a comparison to the Swiss situation. Licensing bodies in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom provide detailed frameworks for WBAs included in their CBME programs. In Canada, the Royal College of Physicians, in cooperation with the Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians, provides clear frameworks for specialist PC education (24, 42, 45, 46). In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) provides clear guidance for PC postgraduate training (33), including recommendations for typical WBAs in a supplementary index (52). Similarly, the UK Royal College of Physicians provides a comprehensive curriculum (47).

In a Swiss postgraduate specialist PC training program, an in-training assessment of competencies can be done using a broad variety of methods. WBAs are an option, among others (43). In Swiss practice, Mini-CEX and DOPS are the most frequently used. For the accreditation of a training site, a minimum of four WBAs per year are required (8).

Tab. 1 and Tab. 2 provide an overview of specialist PC training WBAs in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom compared to Switzerland.

Discussion

We found that WBAs in postgraduate specialist PC training are described mainly in countries where the change to competency-based postgraduate education has been implemented systemically (e.g., Canada). An evaluation of these types of assessments in these settings is lacking, and the literature primarily describes implementation or normative needs (accreditation rules/guidelines). The use of structured WBAs (3) in specialist PC training seems understudied; the only publicly available evidence found in this review is the frameworks or requirements for a curriculum.

Training using WBAs appears to be a good modality in a PC setting for the following reasons: First, healthcare professionals working in PC are often confronted with highly dynamic and unpredictable settings, emphasizing the importance of assessments that take place in real-world environments. The second important aspect of continuity of care offers a natural opportunity for prolonged (multiple-time-point) formative assessments.

The primary intent of WBAs is to increase trainees’ levels of competency in their clinical work environments. Using the experiences of other specialties (53,54), postgraduate specialist training in PC can likely benefit from the introduction of WBAs. Through their communicative, high-feedback, and learner-centered nature, WBAs have the potential to improve postgraduate specialist PC training (especially if used with formative intent).

Countries that pioneered CBME (e.g., the U.S., the UK, and Canada) have a comprehensive program that includes WBAs as the primary assessment modality (see Tab. 1 and Tab. 2), proving their feasibility in these systems. The feasibility of WBAs does not imply universal acceptability, nor is there direct evidence of a training effect or usefulness in increasing the quality of care. Therefore, the lack of specific evaluations of training curricula leaves these questions open.

Swiss specialist PC training, although recently revised, remains close to a time-based model. In the current Swiss setting, only direct (single-time-point) Mini-CEX and DOPS are required; no EPAs are used in Swiss postgraduate specialist PC training (8).

Potential Roles and Impacts of WBAs as a Key Step in Shifting Specialist PC Training from Being Time-based to Competency-based:

The Swiss Example

PC is a relatively young discipline in Switzerland. The Swiss PC system, like other PC systems in Central Europe, has transitioned from a pioneering to a sustainable phase with a time-based training model of training. The reason for this could be that, over the last decade, stakeholders and policymakers have focused on introducing, positioning, and rendering the specialty sustainable at the system level. Presumably, because this achievement necessitates considerable resources, teaching and assessment modalities are left to the discretion of training facilities.

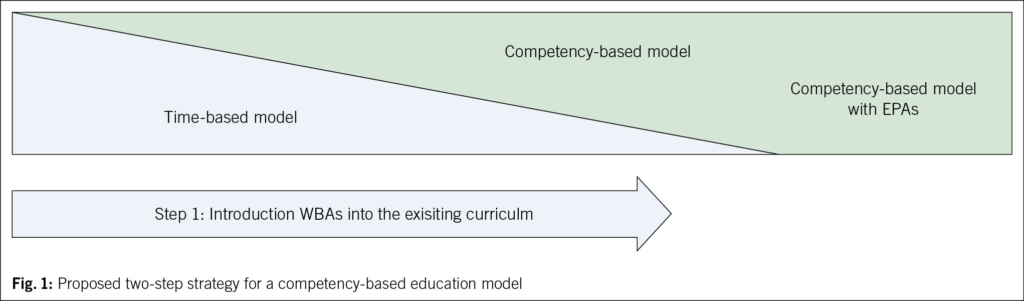

Because WBAs are central to competency-based training (55), we propose a two-step strategy for transitioning to a competency-based model. First, WBAs should be strengthened as standards in existing curricula. Second, existing curricula should evolve further with the introduction of EPAs. A detailed description of the second step is hypothetical and beyond the scope of this review. Fig. 1 summarizes this proposed two-step strategy.

Although the current revision of the specialist training program in Switzerland requires only four WBAs per year, these assessments are still one possibility among many. Therefore, an increase in their role should be considered whenever faculty members’ time resources allow it.

We anticipate several challenges during this transition at the trainee, supervisor, interprofessional team, and patient levels. Trainees and supervisors share the key challenge of additional time requirements. Recent qualitative research on residents’ experiences in CBME-based systems shows that these time requirements, particularly for administrative efforts, are a real issue (56). Together with the universal problem of staff shortages, both at the resident and supervisor levels, this might create tension between clinical responsibilities and education.

This review has several limitations. First, because of its narrative structure, it has inherent limitations regarding structure and rigor; however, we believe that, via the stringent application of SANRA quality items, this review provides a good overview from a practical perspective. Second, the contexts are confined to the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada as examples of CBME-based systems. Switzerland can be considered an example of a transition to CBME, and many of its elements are derived from Anglo-Saxon education systems (e.g., Canada).

Conclusion

WBAs are feasible, accepted, and evaluated as formative training modalities in postgraduate training of specialties besides PC. However, although WBAs are seemingly well tailored to PC, the evaluation of WBAs in specialist PC training is lacking.

In Switzerland, postgraduate specialist PC training follows a primarily time-based model, and WBAs play only a marginal role in assessing trainees’ competencies. The transition to a CBME-based training model is ongoing. It is critical that WBAs be incorporated into Swiss (time-based) PC specialist physician training as a next step toward competency-based training.

History

Manuscript received: 24.06.2024

Accepted after revision: 22.01.2025

Abbreviations

WBAs Workplace-based assessments

PC Palliative Care

CBME Competency-based medical education

Mini-CEX Mini-clinical evaluation exercise

DOPS Direct observation of procedural skills

Appendix 1:

Scale for the Assessment of narrative Review Articles (SANRA), Detailed description according to Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Peer Rev [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2022 Dec 15];4(1):5. Available at: https://researchintegrityjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41073-019-0064-8

Appendix 2

Details of the literature search

Search terms for the initial literature search:

Pubmed

– “workplace-based assessment”[Title/Abstract] AND “postgraduate”[All Fields]

– (“palliative care”) AND (“medical education”) Filters: Review, Systematic Review

– (“palliative care”[All Fields] AND “medical education”[All Fields]) AND ((y_10[Filter]) AND (review[Filter] OR systematicreview[Filter]))

– (“Terminal Care”(mh) OR caregiver*(tw) OR bereave* OR inpatient(tiab) OR “attitude to death”(tw) OR “end of life” OR hospice* OR “terminally ill”(tw) OR palliative*(tw) OR “Advance Care” OR palliat OR advanced OR (morphine AND cancer) OR “cancer pain”)AND “Workplace based assessment”. OR “Mini-cex, Clinical Encounter Cards, Clinical Work Sampling, Blinded Patient Encounters Direct observation of procedural skills , Case-based Discussion, MultiSource Feedback”

ERIC

“Postgraduate palliative care education”

Psychinfo

– Palliative and Education

Scopus

(Title-ABS-KEY (palliative) AND education AND postgraduate)

Ongoing Literature Surveillance

PubMed search alert (11/2022 –10/2023)

“Education” AND “Palliative Care”

Specific Google Scholar search (February 2024)

Search terms (014–2024):

– “Workplace-based Assessment in Palliative Care Physicians Training”

– “Postgraduate Training in Specialist Palliative Care”

Universitäres Zentrum für Palliative Care

Inselspital Bern

Freiburgstrasse

3010 Bern, Schweiz

HFR Tafers

Abteilung Innere Medizin

1712 Tafers

andreas.ebneter@h-fr.ch

The authors have not declared any conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

• Arbeitsplatzbassierte Assessments (AbAs) sind gut validierte Instrumente, um die Kompetenzen von Weiterzubildenden zu verbessern.

• AbAs sind ein essenzieller Bestandteil der kompetenzbasierten medizinischen Weiterbildung und werden in der Palliative Care vor allem in angelsächsischen Ländern eingesetzt.

• Im Schweizer Weiterbildungssystem, welches größtenteils zeitbasiert ist, besteht ein Potential, mit den AbAs den Anteil an kompetenzbasierter Weiterbildung in der spezialisierten palliativmedizinischen Weiterbildung zu erhöhen.

1. Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T: Experiential learning: AMEE Guide No. 63. Med Teach 2012; 34: e102–15.

2. Cherny N, Portenoy RK: Core concepts in palliative care. In: Cherny N, Fallon M, Kaasa S (Hrsg.). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. Oxford university press; 2021.

3. Norcini J, Burch V: Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Med Teach 2007; 29: 855–71.

4. Martin L, Blissett S, Johnston B, Tsang M, Gauthier S, Ahmed Z, u. a.: How workplace based as-sessments guide learning in postgraduate education: a scoping review. Med Educ 2022;

5. Massie J, Ali JM: Workplace-based assessment: a review of user perceptions and strategies to address the identified shortcomings. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2016; 21: 455–73.

6. Ten Cate O, Balmer DF, Caretta-Weyer H, Hatala R, Hennus MP, West DC: Entrustable Profession-al Activities and Entrustment Decision Making: A Development and Research Agenda for the Next Decade. Acad Med 2021; 96: S96–104.

7. Swiss society of Palliative Care (palliative.ch),: Interdisziplinärer Schwerpunkt Palliativmedizin – palliative.ch (Internet). (zitiert 2023 Jan 11); https://www.palliative.ch/de/was-wir-tun/fachgruppen/fachgruppe-aertzinnen-und-aerzte/ids-palliativmedizin; zugegriffen: 11.01.2023

8. Swiss society of Palliative Care (palliative.ch),: Postgraduate Training program for palliative medi-cine (Internet). 2023 (zitiert 2024 Feb 23); https://www.siwf.ch/files/pdf17/palliativmedizin_version_internet_d.pdf; zugegriffen: 23.02.2024

9. Swiss institute for medical education,: Kompetenzbasierte ärztliche Weiterbildung (Internet). (zitiert 2023 Dez 27); https://www.siwf.ch/siwf-projekte/cbme.cfm; zugegriffen: 27.12.2023

10. Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S: SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev 2019; 4: 5.

11. Casarett DJ: The future of the palliative medicine fellowship. J Palliat Med 2000; 3: 151–5.

12. Case AA, Orrange SM, Weissman DE: Palliative medicine physician education in the United States: a historical review. J Palliat Med 2013; 16: 230–6.

13. Sarpal A, Schulz VN, Gofton TE: A Pilot Cross-Discipline Evidence-Based Palliative Care Curriculum for Postgraduate Medical Trainees. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60: 678-687.e3.

14. Shaw EA, Marshall D, Howard M, Taniguchi A, Winemaker S, Burns S: A systematic review of postgraduate palliative care curricula. J Palliat Med 2010; 13: 1091–108.

15. LeGrand SB, Walsh D, Nelson K, Zhukovsky DS: Development of a clinical fellowship program in palliative medicine. J Pain Symptom Manage (Internet) 2000; 20: 345–52. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0033793664&doi=10.1016%2fS0885-3924%2800%2900210-4&partnerID=40&md5=e9d1bf34643b454b3a203400fb8d1e57

16. Landzaat LH, Barnett MD, Buckholz GT, Gustin JL, Hwang JM, Levine SK, u. a.: Development of Entrustable Professional Activities for Hospice and Palliative Medicine Fellowship Training in the United States. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54: 609-616.e1.

17. Cairns W, Yates PM: Education and training in palliative care. Med J Aust (Internet) 2003; 179: S26–8. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0141706859&doi=10.5694%2fj.1326-5377.2003.tb05573.x&partnerID=40&md5=ac4223ba665fa9971f6d4202ab12a88d

18. Boakes J, Gardner D, Yuen K, Doyle S: General practitioner training in palliative care: An experien-tial approach. J Palliat Care (Internet) 2000; 16: 11–9. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0034199146&doi=10.1177%2f082585970001600203&partnerID=40&md5=34d273b82e739475aef635cad79532aa

19. Duong PH, Zulian GB: Impact of a postgraduate six-month rotation in palliative care on knowledge and attitudes of junior residents. Palliat Med 2006; 20: 551–6.

20. Dowell L: Multiprofessional palliative care in a general hospital: education and training needs. Int J Palliat Nurs (Internet) 2002; 8: 294–303. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0036596479&doi=10.12968%2fijpn.2002.8.6.10500&partnerID=40&md5=5ec7af1b8a0975bc9ddaeef8e5a1b924

21. Paal P, Brandstötter C, Bükki J, Elsner F, Ersteniuk A, Jentschke E, u. a.: One-week multidiscipli-nary post-graduate palliative care training: an outcome-based program evaluation. BMC Med Educ (Internet) 2020 (zitiert 2022 Nov 2); 20: 276. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02200-7; zugegriffen: 02.11.2022

22. MacMartin MA, Cullinan A, Vergo M, Zarrabi AJ, Arnold RM: Palliative Care Fellowship Training: Are We Training Fellows for Where the Field Is Going? (with Apologies to Wayne Gretzky). J Pal-liat Med (Internet) 2022 (zitiert 2022 Nov 11); 25: 1619–21. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jpm.2022.0388; zugegriffen: 11.11.2022

23. LÖfmark R, Mortier F, Nilstun T, Bosshard F, Cartwright C, Van Der Heide A, u. a.: Palliative Care Training: A Survey of Physicians in Australia and Europe. J Palliat Care (Internet) 2006 (zitiert 2022 Nov 10); 22: 105–10. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/082585970602200207; zugegriffen: 10.11.2022

24. Herx L, Gofton TE, Bromwich C, Downar J, Popowich S, Sirianni G, u. a.: Postgraduate competen-cies for palliative care – a guidance document (Internet). CSPCP: 2019 (zitiert 2022 Nov 30). https://www.cspcp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Pall-Care-Competenices-Postgrad-FINAL-Sept-2019-EN.pdf; zugegriffen: 30.11.2022

25. Pype P, Wens J, Deveugele M, Stes A, Van den Eynden B: Postgraduate education on palliative care for general practitioners in Belgium. Palliat Med 2011; 25: 187–8.

26. Paal P, Brandstötter C, Lorenzl S, Larkin P, Elsner F: Postgraduate palliative care education for all healthcare providers in Europe: Results from an EAPC survey. Palliat Support Care (Internet) 2019; 17: 495–506. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85060595927&doi=10.1017%2fS1478951518000986&partnerID=40&md5=20c73b0f203400fa1ce97c09b1e87861

27. Ens CDL, Chochinov HM, Gwyther E, Moses S, Jackson C, Thompson G, u. a.: Postgraduate palliative care education: Evaluation of a South African programme. S Afr Med J (Internet) 2011; 101: 42–4. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-78751470672&doi=10.7196%2fsamj.4171&partnerID=40&md5=dc525262cb12154fb89d8330747a626f

28. Paulsen K, Wu DS, Mehta AK: Primary Palliative Care Education for Trainees in U.S. Medical Resi-dencies and Fellowships: A Scoping Review. J Palliat Med 2021; 24: 354–75.

29. Spiker M, Paulsen K, Mehta AK: Primary Palliative Care Education in U.S. Residencies and Fellow-ships: A Systematic Review of Program Leadership Perspectives. J Palliat Med 2020; 23: 1392–9.

30. Bradley CT, Webb TP, Schmitz CC, Chipman JG, Brasel KJ: Structured teaching versus experiential learning of palliative care for surgical residents. Am J Surg 2010; 200: 542–7.

31. Arnold R: The challenges of integrating palliative care into postgraduate training. J Palliat Med (Internet) 2003; 6: 801–7. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-1542644926&doi=10.1089%2f109662103322515392&partnerID=40&md5=c0639d336778f9df5ab37a8f922f5dcb

32. Carmody S, Meier D, Billings JA, Weissman DE, Arnold RM: Training of palliative medicine fellows: A report from the field. J Palliat Med (Internet) 2005; 8: 1005–15. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-27644525122&doi=10.1089%2fjpm.2005.8.1005&partnerID=40&md5=abdd3486ff74d0606893877c3dcc79a1

33. ACGME: ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Educatoin in Hospice and Palliative Medicine (Fellowships) (Internet). https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/540_hospicepalliativemedicine_2023.pdf

34. Gamondi C, Larkin P, Payne S: Core Compentencies in palliative care: an EAPC White Paper on palliative care educatoin -. part 2. Eur J Palliat Care (Internet) 2013 (zitiert 2022 Dez 4); 20. https://www.sicp.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/6_EJPC203Gamondi_part2_0.PDF; zugegrif-fen: 04.12.2022

35. Gamondi C, Larkin P, Payne S: Core Competencies in palliative care: An EAPC White Paper on palliative care education – part 1. Eur J Palliat Care (Internet) 2013 (zitiert 2022 Dez 4); 20. http://www.professionalpalliativehub.com/sites/default/files/EJPC20%282.3%29_EAPC-WhitePaperOnEducation.pdf; zugegriffen: 04.12.2022

36. Myers J, Krueger P, Webster F, Downar J, Herx L, Jeney C, u. a.: Development and Validation of a Set of Palliative Medicine Entrustable Professional Activities: Findings from a Mixed Methods Study. J Palliat Med (Internet) 2015 (zitiert 2022 Dez 9); 18: 682–90. http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jpm.2014.0392; zugegriffen: 09.12.2022

37. Dlubis-Mertens K: Fort- und Weiterbildung in der Palliativversorgung (Internet). (zitiert 2022 Dez 4); https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/weiterbildung/fort-und-weiterbildung-in-der-palliativversorgung.html; zugegriffen: 04.12.2022

38. Dlubis-Mertens K: Kernkompetenzen in der Palliativversorgung (Internet). (zitiert 2022 Dez 4); https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/weiterbildung/kernkompetenzen-in-der-palliativversorgung.html; zugegriffen: 04.12.2022

39. Gagnon B, Boyle A, Jolicoeur F, Labonté M, Taylor K, Downar J: Palliative care clinical rotations among undergraduate and postgraduate medical trainees in Canada: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open (Internet) 2020 (zitiert 2022 Dez 1); 8: E257–63. http://cmajopen.ca/lookup/doi/10.9778/cmajo.20190138; zugegriffen: 01.12.2022

40. Health Service Executive (HSE) Quality and Patient Safety Directorate, Ryan K, Connolly M, Ain-scough A, Crinion J, Hayden C, u. a.: Palliative Care Competence Framework (Internet). Dublin; Palliaitve Care Copmetence Framework Steering Group: 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/10147/323543

41. Schaefer KG, Chittenden EH, Sullivan AM, Periyakoil VS, Morrison LJ, Carey EC, u. a.: Raising the bar for the care of seriously ill patients: results of a national survey to define essential palliative care competencies for medical students and residents. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll 2014; 89: 1024–31.

42. RCPSC: Objectives Of Training in The Subspeciality of Adult Palliative Medicine. 2016;

43. Swiss society of Palliative Care (palliative.ch),: Kompetenzen für Palliativmediziner Logbuch.

44. Swiss society of Palliative Care (palliative.ch),: Kompetenzen für Spezialisten in der Palliative Care. 2012 (zitiert 2022 Dez 4); https://www.palliative.ch/public/dokumente/was_wir_tun/arbeitsgruppen/swisseduc/Kompetenzen_fuer_Spezialisten_in_Palliative_Care.pdf; zugegriffen: 04.12.2022

45. Royal college of Physician and Surgeons of Canada: Subspeciality Training Requirements in Adult Palliative Medicine. 2017;

46. Royal college of Physician and Surgeons of Canada: Standards of Accreditation for Residency Pro-grams in Palliative medicine (adult). 2017;

47. Royal college of Physician: Curriculum for Palliative Medicine Training (Internet). 2022 (zitiert 2022 Nov 26); https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/sites/default/files/Palliative%20Medicine%202022%20curriculum%20FINAL.pdf; zugegriffen: 26.11.2022

48. Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians: Training Opportunities | CSPCP (Internet). (zitiert 2022 Nov 30); https://www.cspcp.ca/information/training-opportunities/; zugegriffen: 30.11.2022

49. Hui D, De La Rosa A, Chen J, Delgado Guay M, Heung Y, Dibaj S, u. a.: Palliative care education and research at US cancer centers: A national survey. Cancer 2021; 127: 2139–47.

50. Edwards A, Nam S: Palliative Care Exposure in Internal Medicine Residency Education: A Survey of ACGME Internal Medicine Program Directors. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018; 35: 41–4.

51. Vanhanen A, Niemi-Murola L, Poyhia R: Twelve Years of Postgraduate Palliative Medicine Train-ing in Finland: How International Guidelines Are Implemented. Palliat Med Rep 2021; 2: 242–9.

52. ACGME: Supplemental Guide: Hospice and Palliative Medicine (Internet). https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pdfs/milestones/hospiceandpalliativemedicinesupplementalguide.pdf

53. Bodgener S, Tavabie A: Is there a value to case-based discussion? Educ Prim Care 2011; 22: 223–8.

54. Lörwald AC, Lahner F-M, Nouns ZM, Berendonk C, Norcini J, Greif R, u. a.: The educational impact of Mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercise (Mini-CEX) and Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS) and its association with implementation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2018; 13: e0198009.

55. Park YS, Hodges BD, Tekian A: Evaluating the Paradigm Shift from Time-Based Toward Competen-cy-Based Medical Education: Implications for Curriculum and Assessment (Internet). In: Wim-mers PF, Mentkowski M (Hrsg.). Assessing Competence in Professional Performance across Dis-ciplines and Professions. Cham; Springer International Publishing: 2016 (zitiert 2024 Feb 13). 411–25.http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-30064-1_19; zugegriffen: 13.02.2024

56. Szulewski A, Braund H, Dagnone DJ, McEwen L, Dalgarno N, Schultz KW, u. a.: The Assessment Burden in Competency-Based Medical Education: How Programs Are Adapting. Acad Med 2023; 98: 1261–7.

PRAXIS

- Vol. 114

- Ausgabe 3

- März 2025