- Limitations of Trainings in Cross-Cultural Competence – The Practitioner Perspective

Objective: Trainings in cross-cultural competence1 are of increasing importance for psychotherapists in order to provide adequate mental health care for patients with a migration background. Yet, little is known about practitioners´ perspectives on working with migrants. Method: Problem-centered interviews with 30 practitioners offering psychotherapy within the German mental health care system have been analyzed using Grounded Theory Methodology to get an insight into practitioners´ experiences with cross-cultural work.

Results: Practitioners have to deal with strong feelings of insecurity in their cross-cultural work. Feelings of insecurity were influenced by practitioners’ underlying cultural concepts, how specific they perceived the cross-cultural contact to be and how they saw themselves in their professional role as psychotherapists. Interestingly, the analysis shows that trainings in cross-cultural competence which mainly convey “culture specific” knowledge on a rather theoretical level might even increase practitioners’ feelings of insecurity.

Conclusions: Conventional teaching formats in cross-cultural competence might not provide psychotherapists with sufficient space to reflect on their insecurities, their “cultural concepts”, and their expectations of themselves in their professional role. Therefore, other settings are required. Dealing with practitioners’ perceived lack of knowledge in the context of culture could be an effective starting point to deal with cross-cultural insecurities.

Practicing psychotherapists are confronted with an increasing number of patients with a migration background2 in their daily work – not only in Germany. This upward trend reflects the worldwide development of migration: In 2015, the United Nations (UN) stated that the number of international migrants (persons living in a country other than where they were born) reached 244 million for the world as a whole − which is an increase of 41 per cent compared to 2000. In addition, the current report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) stated that the number of refugees and asylum seekers reached a regrettable record in 2015 with 65 million people leaving their home countries due to war, conflicts, and expulsion worldwide. The impact on the mental health of migrants remains unclear to date (Moussavi et al., 2007). Epidemiological studies show that the risk of mental health problems is at least as high for migrants as it is for non-migrants (Machleidt & Calliess 2005), some studies found a higher risk of mental health problems among migrants (Bhugra et al., 2014).

Migrants as Mental Health Care Users – The Example of Germany

In 2016, 22.5 percent of the German population could be identified as persons with a migration background – the highest share in German history so far (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2017). According to current data of the annual report of the Migration Integration Policy Index (MIPEX), Germany’s migrant health policy is only partly successful, with Germany ranking 22nd below average compared to other countries (MIPEX, 2015). Health care for migrants in Germany seems particularly deficient in the field of mental health care. The few studies investigating the utilization of the German mental health care system found that immigrants are still inadequately treated (Koch, Küchenhoff, & Schouler-Ocak, 2011). So-called divergent ‘cultural concepts’ and health beliefs are discussed as challenges for mental health care providers as they may provoke feelings of uncertainty, expectations of communication difficulties as well as reservation and might thus lead to a refusal to treat patients with a migration background (Dreißig, 2015; Mösko, Gil-Matinez, & Schulz, 2012).

Reception of the international Discourse on Multiculturalism and Diversity in Germany

In summary, the professional discourse on the importance of multiculturalism and diversity especially in the disciplines of psychology and medicine clearly started earlier in the Anglo-American countries compared with Germany. Indeed, the constructs of race, culture, and intergroup relationships have been research areas for psychologists since nearly the beginning of psychology (e.g. Allport, 1954). Since 1973, the American Psychological Association (APA) has maintained that the provision of multiculturally competent mental health staff is an ethical imperative (Korman, 1974). Prior to the introduction and approval of the Multicultural Guidelines of the APA (2003), several critical foundational publications provided a framework and a starting point that have influenced professional discourse on the importance of multiculturalism and diversity in the field (e.g. Arredondo, 1998; Atkinson, Morten, & Sue, 1979; Sue Arredondo, & McDavis, 1992; Sue & Sue, 1998; for a brief historical overview of multicultural counseling see Baruth and Manning, 2016).

Even though Germany has been a destination for immigrants since many years, it was not politically recognized as „country of immigration“ until 1999 (Ausländerbeauftragte der Bundesregierung, Bundesministerium des Inneren, 1999). This fact is discussed as possible reason for the comparatively late begin of research activities in the field of mental health improvement for migrated patients and cross-cultural competencies (Rommelspacher, 2008).

Subsequently, clinicians and researchers have increasingly demanded a greater “cross-cultural opening” of the mental health care services in Germany with the result that several guidelines were developed (e.g., The Sonnenberger Guidelines) to improve the focus on migrants’ needs and to provide orientation for mental health care professionals (Machleidt & Sieberer, 2013). Cross-cultural competencies of mental health care professionals have been discussed as an essential factor in the debate about adequate treatment for migrants with mental health problems (DGPPN, 2012, 2016). But, up to now, curricula for students of psychology, medicine, nursing and social work do not generally include lectures and course work on cross-cultural competence in health care provision, as they do for example in the Anglo-American countries (Fuentes & Shannon, 2016; Kirmayer et al., 2011; Quirk, 2012). Post-graduate training in the mental health care professions in Germany does not include this subject regularly either. The few existing training programs in cross-cultural competence in Germany derive from the Anglo-American countries. They are adapted to the local mental health care systems (Beach et al., 2005) and not sufficiently evaluated (Anderson, Scrimshaw, Fullilove, Fielding, & Normand, 2003). Currently, evaluated training programs to improve those competencies are lacking in Germany. One new training program to improve cross-cultural competencies in Germany was based on the conception of cross-cultural competence according to Sue et al., 1992 (Reichardt et al., 2017).

The Concept of Cross-Cultural Competence

In psychological or medical theory and research on cross-cultural competence, a lot of different definitions of the concept “cross-cultural competence” are used. Often, a so-called static conception of culture is assumed (Steinhäuser, Martin, von Lersner, & Auckenthaler, 2014). Certain approaches have criticized the concept of cultural competence because of its separation of multiculturalism and social justice by focusing on acquiring knowledge about „other“ cultures and assuming a static concept of culture. To overcome this, it was suggested to foster a critical consciousness of the self, others, and the world, and to support the awareness for concerns of social justice (Kumagi & Lyoson, 2009). A rather systemic constructivist understanding of culture, as suggested for example by Ahmad and Reid (2009), questions the idea that culture is „a thing people ‚have‘“ (p.2). Humanistic psychotherapies have coined the term “contextualism” for this approach (Comas-Diaz, 2012; Schneider, Pierson, & Bugental, 2014). When recognizing the relevance of context, a patient’s individual perspective becomes more important and a less ethnocentric psychological theory is needed to interpret a client’s behavior. Compatible with this, it was argued that psychotherapists should consider cross-cultural competence at the level of agency and institution and should pay greater attention to the influence of socio-political systems in individual functioning and therapy processes (see for example Dadlani & Scherer, 2009; Kirmayer, 2007; see also the concept of Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies by Ratts, Singh, Nassar, McMillan, Butler, & McCullough, 2016). The term cultural humility as a therapeutic framework is used frequently. Instead of focusing on skills and knowledge about different cultures, it rather emphasizes the need for change in attitude (in lifelong learning processes), the necessity to be aware of power imbalances as well as to be humble in every interaction with everyone (Davis et al., 2018; Mosher et al., 2017; Owen et al., 2015). Furthermore, considerations concerning adequate learning formats for cultural competencies led to the result that „a one-size-fits-all approach“ to cultural competences is destined to fail (Adames, Fuentes, Rosa, & Chavez-Dueñas, 2013).

The Perspective of Mental Health Care Professionals

Little is known about how psychotherapists themselves experience the cross-cultural setting and what they consider to be helpful (Hays, 2009). There is evidence deriving from international studies that psychotherapists experience varying degrees of distance and separation from their migrated patients. For example, therapists expected a certain language barrier and anxieties about communication before meeting the patient (Bowker & Richards, 2004). Furthermore, professionals mentioned different values between the migrated patient and their therapist, challenges arising from language differences, different conceptions of psychotherapy and so-called “cultural misunderstandings” (Suphanchaimat, Kantamaturapoj, Putthasri, & Prakongsai, 2015). Other study results show that psychotherapists tend to refuse patients with migration background due to language difficulties (42,8 percent) or cultural issues (8,4 percent; Mösko et al., 2013). Still, studies provide inconsistent results about what therapists themselves consider helpful when treating migrated patients: On the one hand, practitioners think that a specific advanced training does not seem to improve treatment. Instead, the required knowledge and sensitivity seems to be gained during contact with the patient (e.g. Vallianatou, Leavey, & Brown, 2007). On the other hand, (mostly quantitative) studies reported that high rates of participants considered trainings in cross-cultural competence to be useful (72 percent). Interestingly, only 9 percent of participants of that study stated that they had already taken part in such a training (e.g. Mösko et al., 2013).

Open Questions and Aim of this Study

The strong importance that cross-cultural competence is ascribed to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in mental health services is not yet reflected in robust evaluation research showing that paying attention to cultural factors really improves clinical services (Tao, Owen, & Imel, 2015). There is still a lack of research focusing on the specific experiences of psychotherapists working in cross-cultural settings and we miss information about what practitioners consider to be helpful (Moleiro, Freire, Pinto, & Roberto, 2018; Owen, 2018). This study aims at examining the perspective of practicing psychotherapists in the cross-cultural setting. How do practitioners experience this work? What are the challenges they encounter when providing treatment to migrated patients? This article seeks to answer these questions by analyzing the experiences of practitioners working with migrated patients – German practitioners will stand as an example.

Methods

Grounded Theory Methodology is both a research paradigm and a set of coding methods that are used to generate inductively a data-grounded theory about an underlying phenomenon (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The steps of data collection, data analysis and theory development interweave.

Data Collection

The initial stage of data collection depends on the basic research interest (here: the subjective view of mental health care professionals on working in a cross-cultural setting). In accordance with Glaser and Holton (2004), the process of data collection is controlled by the emerging theory. Therefore, the researcher cannot plan data collection in advance of the emerging theory. Still, theoretical knowledge about the subject of interest is needed to be able to recognize the relevant data (theoretical sensitivity; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Our theoretical pre-knowledge was reflected in our research team. The process of writing theoretical memos also helped us to increase theoretical sensitivity. Memos are theoretically notes about the data and the conceptual relations between categories (Glaser & Holton, 2004). They contain decisions as well as theoretical ideas and help the authors to reflect their own positions.

Problem-centered interviews (Witzel, 2000) were conducted with mental health care professionals working in different therapy settings (psychiatric hospital, psychotherapeutic outpatient, outreach clinic). The format of problem centred interviews is semi-structured and consists of four instruments: a short questionnaire to query relevant facts, an interview guideline, tape recordings of the discussion and a postscript to note down situational and non-verbal aspects and initial interpretation ideas (see also Kuckartz, 2010). The interview guideline was developed based on the suggestions by Helfferich (2011). She suggests starting with an open brainstorming to collect all relevant questions to the research question. Then, gradually the questions are filtered, selected, and ordered while frequently approving their contribution to the research question. Helfferich suggests including different types of questions to the interview guideline: core questions (formulated as open as possible to enable the interviewee to talk freely), questions to support the narrative flow, and concrete questions or comprehension questions. Four open core questions were formulated to stimulate longer narrative episodes: 1. Could you tell me something about the context of your work? 2. Could you tell me something about your work experiences with patients with migration background? 3. What do you consider to be helpful in working with patients with a migration background? 4. What would you recommend for working with migrated patients?

Sampling

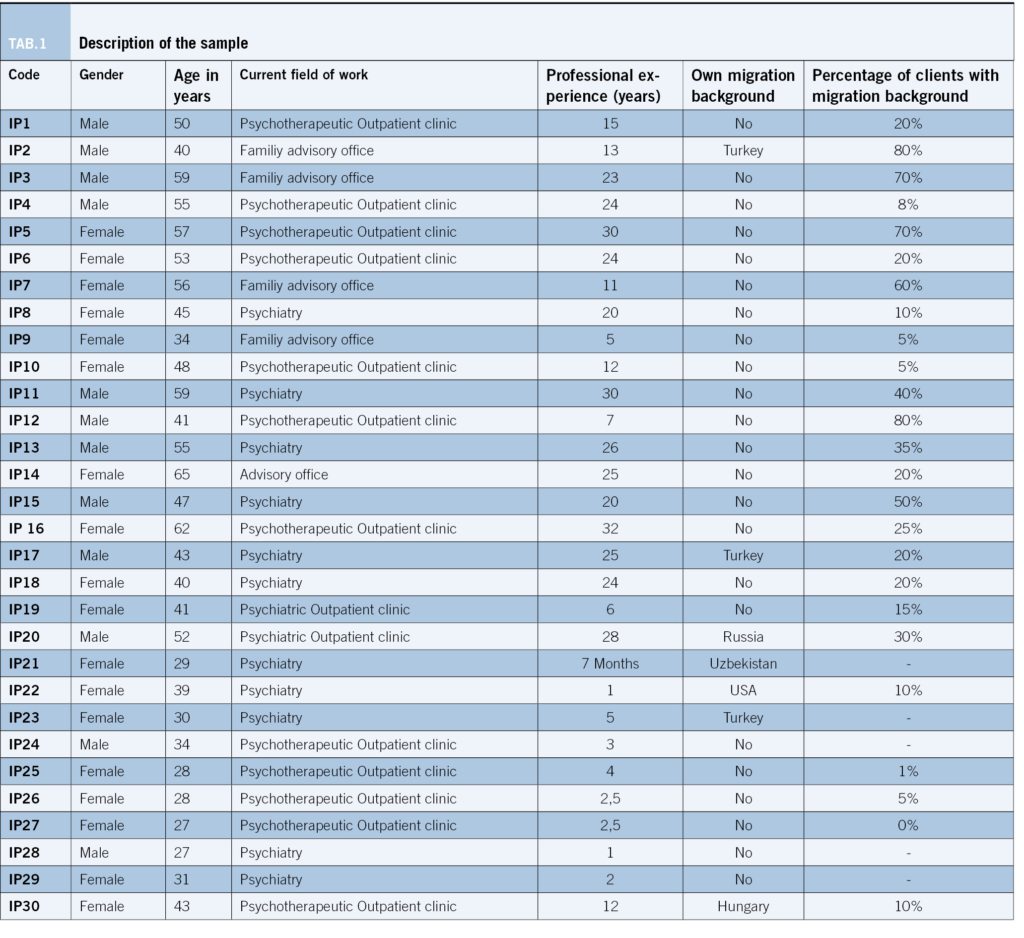

Thirty German mental health care professionals working in therapy-related fields (psychiatric hospital, psychotherapeutic outpatient clinic, outreach clinic, psychological counselling service) were interviewed. To gain a possibly wide range of heterogeneous cases and consequently as much relevant information as possible, we followed the principle of „minimum and maximum contrast“ (Strauss, 1987): individual cases were chosen and compared to one another with respect to their substantive characteristics and features. Participants differed concerning sex, age, psychotherapeutic orientation and years of work experience. All interviewees were working in the German mental health care system as psychotherapists or co-therapists. Ten participants were still in a three to five-year training to become licensed psychotherapists. Twenty participants were already accredited psychotherapists (see table 1).

To recruit participants, a letter providing information about the study and researchers’ contact details was forwarded to therapists at different psychiatric hospitals, psychotherapeutic outpatient clinics and outreach clinics. Similarly, it was sent to different psychotherapy training institutes to reach psychotherapists in training. The interviews were conducted at the working places of the interviewees. The individual interview duration ranged between 60 and 120 minutes. Before the interview, the interviewees’ informed consent was achieved by providing them with information about the purpose and the course of the investigation, the recording of the interviews as well as the transcribing and anonymizing process. The ethical principles of informed consent, confidentiality and avoiding harm were followed rigorously. All personal data as well as any identifying information about the institution were anonymized during the transcription process. In this paper, all quotations taken directly from the interviews are italicized.

Data Analysis

The analyzing process was based on the coding procedures of Grounded Theory Methodology, including open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The first step is data collection to be able to form codes, concepts, and categories. These form the basis for the emerging of a theory. Data analysis contains three steps that are recursive: (1) Open coding. Segments of data were categorized with a short name that at the same time summarized and accounted for each piece of data (Charmaz, 2014). So-called in vivo codes were mainly created. In vivo codes are theoretically rich remarks of interviewees. While sticking closely to concrete utterances, they are still able to explicate the subjective theories manifested in the underlying data (without merely reproducing existing academic theories). The categories that turned out to be the most fitting were chosen to sort, integrate and organize the data material. Then, the codes were formed to preliminary categories which include information about the phenomenon. (2) Axial coding. Axial coding was used to relate categories to subcategories, specify the properties and dimensions of each category, and compile the date we had first fractured during open coding, which allows new ways of understanding the investigated phenomenon (Charmaz, 2014). (3) Selective coding. The final stage of data analysis can be described as the process by which categories are related to a “core category” and the core category systematically being related to the other categories and subcategories while validating those relationships. The category system was validated according to the recommendations of concept building, the constant comparative analysis, building minimal and maximal contrasts, as well as constantly writing and analyzing memos. Data collection and analysis was continued until new material did not generate new information and the category system did not change any more (this is called data saturation; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Preliminary results were repeatedly discussed in a research seminar. Moreover, the research process of collecting and analyzing data was continuously discussed in a research team consisting of four researchers with different professional backgrounds (ethnology, sociology, psychology, economy).

Results

The analysis of 30 interviews resulted in 12605 meaning units. 127 meaning units were deemed unrelated to the subject and therefore were excluded from analysis. The remaining 12478 meaning units were organised and analysed, and finally yielded a model consisting of four categories, of which one was identified as the core category or central phenomenon, named cross-cultural insecurities (1). Three further categories were identified: intervening conditions of cross-cultural insecurities (2), context factors of cross-cultural insecurities (3), and effects of insecurities on emotions and actions (4). The four categories contained of twelve lower-level categories, described below.

Category 1: Cross-Cultural Insecurities

The mental health practitioners of our study experience the cross-cultural setting as unsettling in many ways. The mere information that a patient has a migration background seems to unsettle practitioners in advance. Practitioners described two types of insecurities they experience when treating migrated patients: insecurities regarding their own therapeutic behavior in the cross-cultural setting and insecurities concerning the therapeutic relationship when treating a migrated patient.

Insecurities regarding own therapeutic Behavior in the Cross-Cultural Setting

Insecurities regarding the therapeutic behavior are mainly related to the interventions used during treatment. Practitioners worry if they can use the same techniques for migrated patients that they also use for their other, non-migrated patients. They often reported the feeling of having done something “wrong” during treatment: “She [the patient] was irritated after I asked her about her religion. And that was a moment where I realized: I made a mistake.” (IP2, ll. 59-863).

Insecurities concerning the therapeutic Relationship when treating a migrated Patient

This subcategory includes insecurities about topics that might be taboos. For example, religion was mentioned several times as a topic which practitioners feel a lot of uncertainty about. They are for example worried to ask the wrong questions and to hurt the patient without realizing it. Furthermore, practitioners reported uncertainty concerning their own professional role in the cross-cultural context. They wonder how migrated patients experience their role as practitioners and if the treatment satisfies the patient. Some interviewees stated that they are feeling insecure in a general sense in contact with migrated patients because they were afraid of being or acting racist in some way: “It is a general uncertainty how to behave: How to behave correctly? What is acting in an ethically correct manner? When am I acting racist?” (IP5, l. 746). They fear not to be able to fulfill their patients´ expectations of treatment: “And I felt this pressure: I am the German therapist and I won´t be able to give her what she really needs from me.” (IP5, ll. 396-398). Noteworthy, role-related insecurities were reported mainly by young practitioners who have just started working while the other insecurities mentioned were reported by all practitioners regardless of their work experience.

Category 2: Intervening Conditions of Cross-Cultural Insecurities

We identified conditions that substantially influence practitioners’ insecurities in the cross-cultural setting in its extent. These two subcategories are underlying cultural concepts3 and the experience of the cross-cultural setting as distinct from other therapeutic settings.

Underlying Cultural Concepts

Most interviewees have a static concept of culture rather than a dynamic one. That means, they clearly associate culture with nation and assume cultural groups to which several countries relate. Thus, every human being inherits a certain “culture” from birth. Therefore, the interviewees presupposed that two people from two different countries are “culturally” different in principle. In line with this, “cultural” difference becomes greater the greater the geographic distance between two countries is and stays geographically fixed: “You have a patient and he has slit eyes. And he comes from China. Or somewhere else. Then you reason: this patient ticks differently. If you have patients coming from the US, he or she ticks almost the same as I do. That means, it is much less visible. But they- really, they do tick differently.” (IP11, ll. 688-691). It seems noteworthy that the interviewees regard the ways a person thinks and feels to be “culturally” determined. Furthermore, professionals believe that culture determines how contact with another person is established, how mental health problems are dealt with and what position an individual holds in society. Observed characteristics (and life circumstances) of a patient are interpreted as characteristic of his or her cultural background: “…women for example, if they are ill and they have another cultural background, they may moan much loader. It is just their cultural background that makes them moan that loud.” (IP 5, l. 1145). In the interviews, the question often arose whether patients’ behavior or way of thinking is culturally or individually determined. Practitioners hope to get orientation and certainty about treatment by answering this question.

The Experience of the cross-cultural Setting as distinct from other therapeutic Settings

All interviewees consider the encounter with migrated patients to be different from encountering non-migrated patients and they regard the fact of the patient’s migration background to be an issue in their treatment. For some practitioners it seems to be an essential topic in treatment even though the patient does not specifically mention it as important: “[…] well, I cannot imagine that it [the migration background] doesn´t affect a person or that it is not a topic at all […]” (IP1, ll. 476-477). Others think that it does make a difference, but rather a small one: “[…] I think, the difference is not big. And I wouldn´t make much of a difference, just because there are some cultural differences.” (IP7, ll. 392-398). Nevertheless, a patient’s migration background never goes unnoticed by therapists and some therapists mentioned how surprised they were after treatment that the migration background was hardly ever discussed. Practitioners expect patients with migration background to bring foreign topics into the (therapeutic) setting, which the practitioners do not know how to deal with. In line with this, practitioners expounded the problem of different values and attitudes between their migrated patients and themselves, which, in their opinion, increases the distance within the therapeutic relationship. Also, practitioners assumed a lack of knowledge on the side of migrated patients of how treatment (e.g., psychotherapy) works and therefore expect migrated patients to have unrealistic expectations of treatment. Practitioners reported that they sometimes feel forced to act against their own values and to accept unacceptable behavior to solve situations, e.g., accepting family members as interpreters. Besides that, practitioners reported that migrated patients come to treatment with a lot of socially determined problems (e.g., unemployment), more than other, non-migrated patients. Another difference that practitioners found in patients with migration backgrounds is the patients’ basic expectation of being discriminated against by the practitioners and the whole mental health care system. The differences practitioners perceive convince them that treating patients with a migration background must be – somehow – different and that there is need for something special as the following quotation shows: “[…] it is clearly not enough to just face them [patients with migration background] normally, but one requires a certain sensitivity for their culture […]” (IP6, ll. 684-686). Noteworthy, if practitioners have a static cultural concept and consider the “cultural” background of a patient to be important in their treatment, they reported more insecurities since they feel more (emotionally) distant from the patient and attribute this to the different “cultural” background, which they could not overcome. Accordingly, they assume a definite (theoretical) knowledge to be a prerequisite for the treatment of a patient from that “culture”. This may, obviously, result in the conviction of not being well-prepared (i.e. lacking sufficient theoretical knowledge about a certain nation) and therefore not having enough competencies to treat migrated patients adequately.

Category 3: Context Factors of Cross-Cultural Insecurities

Four lower-level categories were identified that influence practitioners’ feelings of insecurity in a more contextual manner. That means that these categories impact feelings of overstrain in a more subtle and implicit way.

The medical Model of Psychotherapy

The data indicate that the interviewees base their work upon assumptions that derive from a medical model of psychotherapy (for example criticized by Wampold & Imel, 2015). That means that they focus on the psychological disorder of their patient and use psychological explanatory models for the disorder. Within these models, theoretical knowledge allows for assumptions of how changes of the disorder are possible. Furthermore, success of a certain treatment is considered to be based on the interventions of the professional. That may explain why the interviewed practitioners, especially if they work without a team, reported that they do not feel prepared for dealing with the mostly socially determined problems of their (migrated) patients. They do not feel confident about questions of referral (Which institutions are competent in dealing with certain social questions?) and do not think they have access to a professional network: “There are not enough institutions for these people [migrated patients], we have not enough knowledge, not enough network. It is so sad.” (IP17B, l. 473). There is high insecurity regarding laws and political decisions (e.g. concerning financing interpreters) among the interviewees and they reported a lack of time to keep their knowledge constantly up to date. One interviewee stated, migrated patients do not need „real psychotherapy, but rather contact and information.“ (IP17, l. 320).

The public and scientific Discourse on Migration

The interviewees reported that they follow the public and scientific debates on migration through the media, professional journals, and related events in the scientific community. The analysis of the data shows that the practitioners’ view of patients with migration backgrounds seems to be strongly influenced by the current public and scientific discourse on migration. The data indicate that they seem to have a clear picture of migrated individuals in Germany as not having been integrated successfully into German society. Some interviewees considered this lack of integration to be the main reason for mental distress: “That is the problem: that they are not fully integrated into society. Of course, they develop mental health problems. But these are all resultant problems deriving from, for the most part, integration problems.” (IP7, ll. 229-232). They assumed that migrated people face hard times finding work and housing and getting settled in Germany. Furthermore, therapists seem to be convinced that migrated persons have no or only few options to influence their life conditions. Instead they face daily anticlimax, barriers and disadvantages in their attempts to be integrated into German society: “I maintain that our society is profoundly racist. And that´s why every migrated patient is used to encounter racism everywhere. That´s a problem for our work. Some even ask this: ‘I would like to know if you are racist.’” (IP1, ll. 425-433). The interviewees believe that migrated people, especially their patients, have to deal with discrimination by individuals and by the system: “[…] and I still remember this – insults or something like this [by colleagues].” (IP5, ll. 1212-1213). They reasoned that this might lead migrated patients to develop extraordinary expectations as far as their psychotherapeutic treatment is concerned, and they do not dare to limit patients’ expectations as they are used to do with other clientele.

Mental Health Care Structures in Germany

Practitioners problematized the relationship between migrated patients and the mental health care system: they are convinced that migrated patients are not treated adequately, and they see many barriers for migrated patients to get into the mental health care system: low levels of education and insufficient knowledge of the German language, fears of stigmatization and reservations concerning the mental health system. Furthermore, practitioners seem to accept that the mental health care situation for migrated patients is worse than for non-migrated patients − they consider the mental health care structures to be responsible for the unsatisfactory conditions. But in their view, effecting the necessary reforms as individuals seems impossible: “[…] but I think they [migrated patients] benefit worse from the wards. It is normal that patients who have a migration background do not really benefit from the treatment as—and this is accepted […]” (IP4, ll. 1316-1328).

The Practitioner’s Construction of their professional Role

There is evidence in the data that practitioners often see themselves as representatives of society. Some statements of the interviewees indicate that they feel a huge responsibility not only for dealing with mental disorders but also as ‘midwife of integration’. They feel responsible not only to help migrated patients ease their symptoms but also to help them become integrated into German society. Some practitioners state that they feel responsible to repair the deficits that politics and society have caused. The data indicate an intrinsic demand on themselves to treat everyone equally (and to avoid any discrimination) regardless of diagnosis or culture. The data show practitioners very high sense of responsibility to be helpful in their work and to act as ‘bridge builders’ for migrated patients in particular: “One needs to reach the patients. That´s important. No? And to tear down barriers, to build bridges, and you achieve this by informing them that we exist.” (IP7, ll. 621-623). It seems that they feel trapped between the demands of their migrated patients and the expectations placed on them by society, politics and – not least – by themselves.

Category 4: Effect of cross-cultural Insecurities on Practitioners Emotions, Attitudes, and Behavior

Several consequences of practitioners’ insecurities on their emotional reaction, their attitudes, and resulting behavior emerged from the data and resulted into four lower level categories.

Effects on Practitioners emotional Reactions

The data indicate that the insecurities experienced by practitioners are associated with different emotional reactions. Practitioners reported that treating migrated patients is associated with an increase of work in different ways: possible language problems require extra effort, especially because they have no or very little experience in working with translators. Even more, they report many concerns about engaging them. Practitioners find that migrated patients do not have the same psychological explanatory models as they do so that they feel the need to “teach” the patients, which seems to be arduous and exhausting: “It was educational work.” (IP17B, l.189). Some practitioners reported that working with migrated patients increases their workload to such an extent that they reach their personal limits. Moreover, building a therapeutic relationship with migrated patients is associated with more time and even with more economic resources. As a result, practitioners reported that they do not feel satisfied with the quality of their work in the cross-cultural setting; instead, they often feel helpless and overwhelmed by a societal responsibility they are ill-equipped to deal with. Moreover, they reported feelings of shame since they feel insufficient due to a lack of “culture” specific knowledge. They seem to feel responsible not only for treating mental health problems, but for making the migrated patients “fit” for integration. One interviewee described himself as “a poor little psychotherapist” (IP7, l. 518) who seems to be in charge of the deficits politics and the society had caused. Some interviewees stated that these thoughts evoke frustration and aggression.

Effects on Practitioners Behavior towards treating migrated Patients

Practitioners reported that they behave differently because of this situation: some statements indicate that the practitioners lose interest in the cross-cultural topic, which might lead to a refusal to treat migrated patients at all: “Yes, I had more work with him [a migrated patient] in the beginning. I had to teach him the whole and needed to explain what it all is about and so on. Of course, it was a barrier.” (IP1, ll. 761-764). Others stated that they did not feel like treating migrated patients because they considered the therapy to be exhausting: “[…] because I can choose the patients I want to treat and because I do not feed like treating this clientele. It is just that you can only talk with them with a translator. And that is difficult. And even if they are differentiated, it still is very exhausting. Very exhausting.” (IP11B, ll. 83-89). Others stated that they would rather refer migrated patients to other institutions. Another result of our investigation is that practitioners become more and more uncertain about acting in an adequate way and feel increasingly irritated by their migrated patients’ needs.

Practitioners Attitudes to Patients Needs

Practitioners attitudes towards needed competencies for a (cross-cultural) treatment may result from practitioners perceptions of what patients need for a successful treatment. Even though practitioners generally believe that a migration background must play a role in treatment, two different opinions of what migrated patients need for an adequate treatment were discernible: some practitioners are convinced that there is no need for any specific competency to treat migrated patients, while other practitioners strongly believe in the need for specific competencies or tools.

If practitioners think that there is no need for any specific treatment, they believe in the universal needs of every individual instead and consider the same requirements for every patient: feeling understood, supported and taken seriously. In line with this, practitioners believing in the latter think that there is no need to gain any extra theoretical knowledge. In contrast, they emphasized the risks of manualized treatment: “[…] yet everyone is an individual every time, and then the danger is, when you approach it with such a manual, that you then look at him only as a butterfly, a mounted butterfly – such a specimen of his kind. That’s not a good basis for working together.“ (IP1, l. 843). In fact, it seems more appropriate to be open to the topics the (migrated) patients bring up and to ask questions if the patient’s meaning is not understood. Being authentic seems to be more important to them than any specific tool. Common attitudes were mentioned by these practitioners, e.g., appreciation, curiosity, sensitivity and tolerance. In this context, practitioners do not believe that these competencies can be distilled into specific tools or trainings for a particular clientele. Therefore, a seminar in cross-cultural competence appeared almost as a farce to them: “[…] I’m not going to learn that in a seminar in two and a half days, that’s ridiculous. And I then think that’s almost dishonest.” (IP7, l. 529).

Other practitioners believe that specific competencies are needed for adequate treatment and that these competencies can be taught and trained. Usually, they meant rather theoretical knowledge about a specific nation. This knowledge should be gained in seminars, trainings and manuals. Interviewees who ascribe to this view associate an increase of knowledge with an increase of security and orientation within the treatment process. Otherwise, none of the interviewees stated that they would need such specific knowledge or that they would like to attend a seminar in cross-cultural competence themselves. If trainings in cross-cultural competence were considered a helpful solution, the interviewees rather formulated it as a recommendation for younger professionals. Another critical point was that interviewees problematized the lack of voluntariness for advanced trainings in cross-cultural competence. It seemed only helpful for them if one could attend these trainings voluntarily.

Practitioners Attitudes to Requirements for improved Treatment

Whether or not practitioners feel the need for specific requirements depends on the importance they attribute to a patient’s migration background. Specific knowledge was seen as a potential solution for a perceived lack of competence, whereas structural changes came into focus when practitioners felt sufficiently competent.

If they wish to improve their competencies, practitioners consider a more intimate setting where they can discuss open questions and experiences with colleagues to be more helpful than a seminar or training. They wish to reflect on stereotypes and the process of stereotyping and hope to get thought-provoking impulses: “[…] and I would say the confrontation with one’s own prejudices are important. And I wished that to be a provocative process.” (IP1, l. 480). Practitioners also mentioned that they would need more courage to treat migrated patients: to ask the patient questions and to show personal insecurities or lack of knowledge concerning the patient’s experience and country of origin and, by doing so, get into a stable therapeutic relationship with their patients. They wish to be more up to date with the relevant laws and regulations and their implementation. Knowing the local professional networks is seen as a support. Some practitioners believe that they find certainty and orientation in a specific therapeutic concept for migrated patients. All in all, interviewees expressed that they wish to get more support and validation for their work. If practitioners consider lack of integration into German society as a main source of mental health problems for their migrated patients, they see a proper job and German language classes as more important for their patients than their improved competencies as practitioners. Structural, political, and societal changes are needed in their opinion.

Discussion

As described above, cross-cultural competence in psychosocial care has become a more important concern, also in Germany. Some of the interviewees have not received a formal cross-cultural training themselves but draw from their working experience. This study thus may offer the unique chance to document and describe how this competence is developing as psychotherapeutic quality. And, even more interesting, our empirical data from Germany seem to support the theoretical approaches (e.g., the concept of cultural humility), basically deriving from Anglo-American countries, which have not reached the German discourse yet.

First, the implications we derived from the data are presented. They concern practitioners’ insecurities and how to deal with them on the one hand and, on the other hand, the acquisition of cross-cultural competence and how it could be improved. Then strengths and limitations of our study are discussed.

Implication 1: Raising Psychotherapists Capacities to deal with personal Insecurities

Trainings in cross-cultural competence should raise the psychotherapist’s capacities to deal with personal insecurities. We consider this a (life) long learning process in experiential and reflexive learning formats (e.g., supervision, encounter groups).

Our research shows that practitioners face a lot of challenges in cross-cultural encounters and how this might lead to feelings of insecurity and distress. It seems particularly important that practitioners are sensitive to their own emotional reactions when working with patients with a migration background (e.g., feeling uncertain or frustrated) in order to be aware of possible consequences (e.g. refusal of patients, own depletion, higher tendency to stereotype) and in order to find ways to deal with these feelings. It seems necessary, that practitioners meet settings to reflect on their own stereotypes and the function of stereotyping by asking themselves questions such as: Why am I explaining a certain behavior of my patient by his/her cultural background? What is the consequence of this explanation? What is my expectation when treating this patient? The concept of cultural humility is fitting with our results and might provide ways for psychotherapists to work with personal insecurities and to engage in a connection with their clients instead (Davis et al., 2018; Mosher et al., 2017; Owen et al., 2015). Furthermore, our results indicate that practitioners seek to become more encouraged to work with migrated patients. What could be an adequate format to acquire this? Our data question conventional trainings where merely (theoretical) knowledge is taught and learned as a suitable format. This format might give practitioners the impression that specific (theory-based) knowledge and specific tools are needed to treat patients with a migration background and that without them one is not only ill-equipped but also not entitled to do so. It is doubtful to which extent personal feelings of overstraining or insecurities can be contained. Instead, it seems necessary to support a deeper exchange with other practitioners facing the same challenges, e.g., in supervision or supportive professional peer group settings. This idea is supported by studies that show that practitioners rate supervision to be highly beneficial to their professional development (Ronnestad & Orlinsky, 2005). When implementing trainings in cross-cultural competence, the excessive demands of the profession and the limited time resources of practitioners need to be taken into consideration. Otherwise, the training would risk producing the direct opposite of what it intends to achieve (increased feelings of overstraining and therefore a higher chance of refusing to work with this clientele). Our article wishes to encourage practitioners to start talking about the feelings they experience in cross-cultural encounters and ensure support through supervision or supportive professional peer groups.

Implication 2: Fostering a Dynamic and Contextual Model of Psychotherapy

Trainings in cross-cultural competence should foster a dynamic and contextual model of psychotherapy including culture as one aspect among (many) others. A dynamic concept of culture is the absolute prerequisite to overcome one-sided culturalization and stereotyping.

The reflection on one’s own cultural concepts seems to be important, because, as our results show, a static concept of culture may increase the risk of stereotyping and in turn inhibits individualized treatment. If theoretical based seminars are offered, it seems important that “culture” specific knowledge is eluded to avoid one-sided culturalization and stereotyping by imparting a dynamic concept of culture. Practitioners might conclude that stereotyping reduces insecurities because it simplifies reality. But, as our results show, the resulting explanatory models might be oversimplified and rather hinder than help when trying to understand an individual’s behavior, which might in turn increase insecurities.

Furthermore, a different conceptual understanding of psychotherapy, which focuses more on contextualism and holism, might also reduce stereotypes and might help dealing with insecurities because a practitioner’s particular understanding of reality is emphasized (for the contextual model of psychotherapy, see Wampold & Imel, 2015). Our data indicate that a one-sided imparting of rather theoretical culture-specific knowledge might foster the illusion that only theoretical knowledge qualifies for treating migrated patients and could discourage practitioners even further from offering cross-cultural treatment. Instead, practitioners need to reflect on their attitudes concerning their professional role: How does theoretical knowledge impact the way I work with my patients? How do I deal with not knowing? A broader understanding of professional competencies of psychotherapists is needed. The discussions concerning the competency movement (Rubin et al., 2007) or “deliberate practice” (Ronnestad & Skovholt, 2001) may provide helpful suggestions. They emphasize that the development of psychotherapeutic competencies is a long-term and complex learning process. This should be kept in mind when discussing the development of cross-cultural competence.

Implication 3: Building supportive Structures for Psychotherapists

Trainings in cross-cultural competence should focus on building supportive structures for psychotherapists. Trainings in cross-cultural competence should impart migration-related laws and networking opportunities in the cross-cultural context as our results implicate. The discussion about improvements in mental health care for migrated patients should not focus on the individual practitioner and her/his competencies alone. Psychotherapists may regain a feeling of self-efficacy by addressing the structural problems in political actions. In this way they redirect the responsibilities to the causes. In their sessions it may be helpful to mutually address these issues with their patients. This could also decrease the high level of responsibility practitioners feel and would probably make working with this clientele more attractive. Improving the mental health care situation for patients with a migration background by increasing cross-cultural competences of practitioners can only be constructive if the needs of practitioners are taken into consideration.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

One strength of our study is that it examined a unique population (practicing psychotherapists) concerning their experiences in the cross-cultural setting. As far as we know, there is no comparable examination, studying this topic with this certain qualitative approach. Another strength is the comparatively high number of participants (compared with usual numbers of participants in qualitative research designs). Furthermore, our methodical approach (theoretical sampling, which is considered to be a technique of generalizability/ external validity) meets the requirements of Williams’ postulate of “moderate generalization” of our results (Williams, 2002, p.131). Still, our study is exploratory and therefore results need to be carefully interpreted. One of our most salient limitations of the current research is that our sample only comprised psychotherapists working (and being qualified) in Germany. This further limits the representative status of our results. Still, the question of how to deal with feelings of insecurities in the psychotherapeutic encounter seems relevant, independent from the country of origin or the causes of feelings of insecurity. Also, the question of how to deal with stereotypes and prejudices seem an actual and timeless challenge. We hope to be able to stimulate the international discourse on content and format of competence acquisition (what should be trained, and how?) with our empirical material and our resulting implications.

Footnote:

1. In this paper, the construct of being or acting cross-cultural (equally used with the construct of transcultural/ transculturality) is understood in line with Welsch (1999) and is defined to include race, ethnicity, class, gender/sex, religion, sexual orientation, and ability/ disability status. To give one example of a definition of cultural competence: „Multicultural counseling competence is defined as the counselor‘s acquisition of awareness, knowledge, and skills needed to function effectively in a pluralistic democratic society (ability to communicate, interact, negotiate, and intervene on behalf of clients from diverse backgrounds), and on an organizational/ societal level, advocating effectively to develop new theories, practices, policies and organizational structures that are more responsive to all groups.“ (Sue, 2001, p. 802).

2. In Germany ‘migration background’ is a common term in science and in society in general. It refers to all foreigners and naturalized individuals, to those Germans that immigrated to today’s German territory after 1949 as well as to all individuals born in Germany as Germans with at least one migrated parent or a parent born as a foreigner in Germany (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2017, p. 4).

3. With „underlying cultural concept“ we mean the subjective perceptions and assumptions the interviewees have concerning the concept of culture, which is expressed through their statements in the interviews. While a static/ traditional cultural concept is characterized by social homogenization, ethnic consolidation and intercultural demarcation, a dynamic cultural concept tries to pass through classical cultural boundaries and is therefore characterized by hybridization: for every culture, all other cultures have come to be inner-content or satellites (for detailed information concerning the definitions see Welsch, 1999).

MAPP-Institut

Klausener Str. 12

D-39112 Magdeburg

theresa.steinhaeuser@mapp-institut.de

Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie

Arbeitsbereich Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie

Freie Universität Berlin

Habelschwerdter Allee 45

D-14195 Berlin

a.auckenthaler@fu-berlin.de

AG Transkulturelle Psychiatrie/ZIPP Klinik für Psychiatrie &

Psychotherapie, Charité Universitätsmedizin

Charitéplatz 1

D-10117 Berlin

schoedwell@charite.de

1. Adames, H. Y., Fuentes, M. A., Rosa, D., & Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y. (2013). Multicultural initiatives across educational contexts in psychology: becoming diverse in our approach. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 15(1), 1-16.

2. Allport, G.W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

3. Ahmad, S., & Reid, D. (2009, Oct.). Cultivating cultural competence: Understanding and integrating cultural diversity in psychotherapy. [Web article]. Retrieved from http://societyforpsychotherapy.org/cultivating-cultural-competence-understanding-and-integrating-cultural-diversity-in-psychotherapy

4. American Psychological Association. (2003). Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist, 58(5), 377-402.

5. Anderson, L. M., Scrimshaw, S. C., Fullilove, M. T., Fielding, J. E., & Normand, J. (2003). Culturally competent healthcare systems. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 24, 68 – 79.

6. Arredondo, P. (1998). Integrating multicultural counseling competencies and universal helping conditions in culture-specific contexts. The Counseling Psychologist, 26, 592-601.

7. Atkinson, D., Morten, G., & Sue, D. W. (1979). Counseling American minorities: A cross-cultural perspective. Dubuque, IA: Brown Company.

8. Ausländerbeauftragte der Bundesregierung/ Bundesministerium des Innern / Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung (1999). Das neue StaatsangehörigenRecht. Einbürgerung: fair, gerecht, tolerant. Retrieved from http://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Broschueren/nichtinListe/1999/Das_neue_Staatsangehoerigkeitsrecht_-_Id_2243_de.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

9. Baruth, L. G., & Manning, M. L. (2016). Multicultural counseling and psychotherapy: A lifespan approach. Routledge.

10. Beach, M. C., Price, E. G., Gary, T. L., Robinson, K. A., Gozu, A., Palacio, A., … Bass, E. B. (2005). Cultural competency: A systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Medical Care, 43, 356.

11. Bermejo, I., Hölzel, L. P., Kriston, L., & Härter, M. (2012). Subjektiv erlebte Barrieren von Personen mit Migrationshintergrund bei der Inanspruchnahme von Gesundheitsmaßnahmen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt- Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz, 55(8), 944-953.

12. Bowker, P., & Richards, B. (2004). Speaking the same language? A qualitative study of therapists’ experiences of working in English with proficient bilingual clients. Psychodynamic Practice, 10, 459-478.

13. Bhugra, D., Gupta, S., Schouler-Ocak, M., Graeff-Calliess I, Deakin, N.A., Qureshi, A.,… Carta, M. (2014). EPA guidance mental health care of migrants. Eur Psychiatry 29(2), 107–115.

14. Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

15. Comas-Diaz, L. (2012). Humanism and multiculturalism: An evolutionary alliance. Psychotherapy, 49(4), 437-441.

16. Dadlani, M., & Scherer, D. (2009, Nov.). Culture in psychotherapy practice and research: Awareness, knowledge, and skills. [Web article]. Retrieved from http://societyforpsychotherapy.org/culture-in-psychotherapy-practice-and-research-awareness-knowledge-and-skills

17. Davis, D.E., DeBlaere, C., Owen, J., Hook, J.N., Rivera, D.P., Choe, E.,… Placeres, V. (2018). The multicultural orientation framework: A narrative review. Psychotherapy, 55(1), 89.

18. DGPPN (2012). Positionspapier Psychosoziale Versorgung von Flüchtlingen verbessern. Retrieved from https://www.dgppn.de/_Resources/Persistent/7e810b2fd033c8a7d0b13479dc516ad310e11fa1/2012-09-12-dgppn-positionspapier-migration.pdf

19. DGPPN (2016). Positionspapier Psychosoziale Versorgung von Flüchtlingen verbessern. Retrieved from https://www.dgppn.de/_Resources/Persistent/c03a6dbf7dcdb0a77dbdf4ed3e50981431abe372/2016_03_22_DGPPN Positionspapier_psychosoziale%20Versorgung%20Fl%C3%BCchtlinge.pdf

20. Dreißig, V. (2015). Interkulturelle Kommunikation im Krankenhaus: Eine Studie zur Interaktion zwischen Klinikpersonal und Patienten mit Migrationshintergrund. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

21. Fuentes, M. A., & Shannon, C. R. (2016). The state of multiculturalism and diversity in undergraduate psychology training. Teaching of Psychology, 43(3), 197-203.

22. Glaser, B.G., & Strauss, A.L. (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago.: Aldine.

23. Glaser, B.G., & Holton, J. (2004). Remodeling grounded theory. Forum: Qualitative social research, 5. Retrieved from http://www.qualitative research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/607/1315.

24. Hays, P. A. (2009). Integrating evidence-based practice, cognitive–behavior therapy, and multicultural therapy: Ten steps for culturally competent practice. Professional Psychology, 40(4), 354.

25. Helfferich, C. (2011). Die Qualität qualitativer Daten: Manual für die Durchführung qualitativer Interviews. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

26. Kirmayer, L.J. (2007). Psychotherapy and the cultural concept of the person. Transcult Psychiatry, 44, 232-257.

27. Kirmayer L.J, Fung, K., Rousseau, C., Lo, H.T., Menzies, P., Guzder, J., … McKenzie, K. (2011). Guidelines for Training in Cultural Psychiatry. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57, 1-17.

28. Koch, E., Küchenhoff, B., & Schouler-Ocak, M. (2011). Inanspruchnahme psychiatrischer Einrichtungen von psychisch kranken Migranten in Deutschland und der Schweiz. In: D. Domenig (Ed.), Transkulturelle Kompetenz. Lehrbuch für Pflege-, Gesundheits- und Sozialberufe (pp. 489-498). Bern: Hans Huber.

29. Korman, M. (1974). National conference on levels and patterns of professional training in psychology: The major themes. American Psychologist, 29(6), 441-449.

30. Kuckartz, U. (2010). Einführung in die computergestützte Analyse qualitativer Daten. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

31. Kumagai, A. K., & Lypson, M. L. (2009). Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Academic medicine, 84(6), 782-787.

32. Machleidt, W., & Calliess, I. T. (2005). Transkulturelle Psychiatrie und Migration–Psychische Erkrankungen aus ethnischer Sicht. Die Psychiatrie-Grundlagen und Perspektiven, 2(2), 77-84.

33. Machleidt, W., & Sieberer, M. (2013). From Kraepelin to a modern and integrative scientific discipline: The development of transcultural psychiatry in Germany. Transcultural psychiatry, 50(6), 817-840.

34. Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) (2015). Retrieved from http://www.mipex.eu/germany#/tab-health

35. Mösko, M. O., Gil-Martinez, F., & Schulz, H. (2012). Cross-Cultural Opening in German Outpatient Mental Healthcare Service: An Exploratory Study of Structural and Procedural Aspects. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 20(5), 434-446.

36. Mosher, D. K., Hook, J. N., Captari, L. E., Davis, D. E., DeBlaere, C., & Owen, J. (2017). Cultural humility: A therapeutic framework for engaging diverse clients. Practice Innovations, 2(4), 221.

37. Moussavi, S., Chatterj, S., Verdes, E., Tandon, A., Patel, V., & Ustun, B. (2007). Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet, 370, 851–858.

38. Moleiro, C., Freire, J., Pinto, N., & Roberto, S. (2018). Inegrating diversity into therapy processes: the role of individual and cultural diversity competences in promoting equality of care. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 18(2), 190-198.

39. Norcross, J. C. (2011). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Evidence-based responsiveness (2nded.). New York: Oxford University Press.

40. Owen, J. (2018). Introduction to special issue: Cultural processes in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 55(1), 1.

41. Owen, J., Tao, K. W., Drinane, J. M., Hook, J., Davis, D. E., & Kune, N. F. (2016). Client perceptions of therapists’ multicultural orientation: Cultural (missed) opportunities and cultural humility. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 47(1), 30- 37.

42. Quirk, K. (2012, September). Course syllabi lacking in multicultural and social justice training: An article review [Web article] [Review of the article Multicultural competence and social justice training in counseling psychology and counselor education: A review and analysis of a sample of multicultural course syllabi, by A. L. Pieterse, S. A. Evans, A. Risner-Butner, N. M. Collins, & L. B. Mason]. Retrieved from http://www.societyforpsychotherapy.org/multicultural-course-syllabi

43. Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar‐McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28-48.

44. Reichardt, J., von Lersner, U., Rief, W., & Weise, C. (2017). Wie lassen sich transkulturelle Kompetenzen bei Psychotherapeuten steigern? Vorstellung eines webbasierten Trainingsprogramms. Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie, Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 65, 155-165.

45. Rommelspacher, B. (2008). Tendenzen und Perspektiven interkultureller Forschung. In B. Rommelspacher & I. Kollak (Hrsg.), Interkulturelle Perspektiven für das Sozial- und Gesundheitswesen (S. 115-135). Frankfurt a.M.: Mabuse-Verlag.

46. Ronnestad, M., & Orlinsky, D. (2005). Clinical Implications: Training, Supervision, and Practice. In D. E. Orlinsky & M. H. Ronnestad (Eds.), How Psychotherapists Develop: A Study of Therapeutic Work and Professional Growth (pp. 181-201) Washington: American Psychological Association.

47. Ronnestad, M., & Skovholt, M. (2001). Learning Arenas for Professional Development: Retrospective Accounts of Senior Psychotherapists. Professional Psychology, 32 (2), 181-187.

48. Rubin, N. J., Bebeau, M., Leigh, I. W., Lichtenberg, J. W., Nelson, P. D., Portnoy, S., … Kaslow, N. J. (2007). The competency movement within psychology: A historical perspective. Professional Psychology, 38(5), 452.

49. Schneider, K.J., Pierson, J.F., & Bugental, J.F.T. (2014). Humanism and Multiculturalism. The Handbook of Humanistic Psychology: Theory, Research, and Practice. Los Angeles: Sage.

50. Statistisches Bundesamt (2017). Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit. Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund – Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2016. Wiesbaden.

51. Steinhäuser, T., Martin, L., von Lersner, U., & Auckenthaler, A. (2014). Konzeptionen von „transkultureller Kompetenz“ und ihre Relevanz für die psychiatrisch-psychotherapeutische Versorgung. Ergebnisse eines disziplinübergreifenden Literaturreviews. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie, 64, 345-353.

52. Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press.

53. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory publications (2dn ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

54. Sue, D. W. (2001). Multidimensional facets of cultural competence. The Counseling Psychologist, 29, 790–821.

55. Sue, D. W., Arredondo, P., & McDavis, R. J. (1992). Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: A call to the profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70, 477-486.

56. Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (1999). Counseling the culturally different: Theory and practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

57. Suphanchaimat, R., Kantamaturapoj, K., Putthasri, W., & Prakongsai, P. (2015). Challenges in the provision of healthcare services for migrants: a systematic review through providers´ lens. BMC health services research, 15 (1), 390-403.

58. Tao, K. W., Owen, J., Pace, B. T., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). A meta-analysis of multicultural competencies and psychotherapy process and outcome. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(3), 337-350.

59. United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015a). Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2015 revision, United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2015.

60. Vallianatou, C., Leavey, G., & Brown, J. (2007). Practitioners’ perspectives of multicultural sensitivity. Counselling Psychology Review, 22, 58-67.

61. Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z.E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

62. Welsch, W. (1999). Transculturality: The puzzling form of cultures today. Spaces of culture: City, nation, world, 194-213.

63. Williams, M. (2002). Generalization in interpretative research. In T. May (Ed.) Qualitative research in action (pp.125-143). London: Sage.

64. Witzel, A. (2000). The problem- centered interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1, Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1132/2519

Therapeutische Umschau

- Vol. 80

- Ausgabe 7

- September 2023